Collective Action on Corruption in Nigeria : Social Norms Approach to Connecting Society and Institutions, Chatham House

Les auteurs

Chatham House, the Royal Institute of International Affairs, is an independent policy institute based in London. Our mission is to help build a sustainably secure, prosperous and just world.

Leena Koni Hoffmann is an associate fellow of the Africa Programme at Chatham House and technical adviser to the Permanent Inter-State Committee for Drought Control in the Sahel. She was a Marie Curie research fellow at the Luxembourg Institute of Socio-Economic Research (LISER) in 2013–15. Her research focuses on Nigeria’s politics, corruption, food security and regional trade in West Africa.

Raj Navanit Patel is a University of Pennsylvania Penn Social Norms Group (PennSONG) consultant. He is also a PhD candidate in the Department of Philosophy and a member of the Department of Philosophy, Politics, and Economics at the University of Pennsylvania. He worked at the US Department of Homeland Security from 2011–13. His research focuses on normative issues surrounding the provision of public goods.

Link to the original document here.

This report analyses the socially integrated opinions, expectations and behaviors regarding corruption in Nigeria, specifically within the systems of law enforcement and healthcare. Discovering these personal and social beliefs regarding bribery, extortion, embezzlement and nepotism, was the main goal of the survey created by Nigeria’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) and implemented in seven jurisdictions throughout the country (Adamawa, Benue, Enugu, FCT, Lagos, Rivers, Sokoto). While the words ‘corruption’, ‘bribe’, ‘bribery’ and similar terms were not used in the survey, other implementers made it clear to citizen respondents that the questions concerned illegitimate informal methods of payment. The survey investigated whether if in everyday situations where corrupt activity occurs, people believe that others around them behave in certain ways and expect others to behave similarly.

WATHI has focused on this report because it presents in a clear and organized fashion the positive correlation between social norms and the continuation of corruption. While corruption in Nigeria is publicly acknowledged as a rampant and destructive practice with serious consequences for the government as well as its citizens, it remains ever-present and misunderstood. As corruption spreads, basic societal values are broken down and citizens’ sense of moral responsibility is lost. This challenge cannot be regulated by the imposition of anti-corruption laws unless such laws and policies are based on a comprehensive understanding of the societal behaviors, attitudes and norms that allow corruption to persist.

Ce rapport met en évidence les opinions, les attentes et les comportements socialement intégrés concernant la corruption au Nigéria, en particulier dans le secteur de la justice et de la santé. La découverte de ces croyances personnelles et sociales en matière de corruption, d’extorsion, de détournement de fonds et de népotisme a fait l’objet d’un sondage initié par le Bureau national des statistiques du Nigéria (NBS) et mis en œuvre dans sept juridictions du pays (Adamawa, Benue, Enugu, FCT, Lagos , Rivers, Sokoto). Même si les termes de «corruption», de «pot-de-vin» et d’autres termes similaires n’ont pas été utilisés dans l’enquête, les enquêteurs ont clairement indiqué aux citoyens interrogés que les questions portaient sur les méthodes de paiement illégitimes. Le sondage examine des situations de la vie quotidienne dans lesquelles des activités de corruption peuvent se produire. L’enquête montre que Les gens pensent que ceux autour d’eux adoptent des comportements allant dans le sens de la corruption et s’attendent à ce que les autres se comportent de manière similaire.

WATHI a également choisi ce rapport car il présente de manière claire et organisée la corrélation entre les normes sociales et le phénomène de la corruption. La corruption au Nigéria est publiquement reconnue comme une pratique répandue et destructrice. Elle présente de graves conséquences pour l’État et ses citoyens mais elle demeure un phénomène généralisé et mal appréhendé au sein de la société. Au fur et à mesure que la corruption se propage, les valeurs fondamentales de la société sont dégradées et le sentiment de responsabilité morale des citoyens est remis en cause. Ce défi ne peut être relevé que par la mise en place de lois anticorruption plus efficaces qui se fondent sur une compréhension globale des comportements, des attitudes et des normes sociétales qui permettent la persistance de la corruption.

This report works to identify the specific social norms and collective practices in Nigeria that contribute to the continued corruption on both a national and local level throughout the country. Once identified and better understood, targeted and more effective policies may be put in place to change such degrading practices. While the report focuses solely on different forms of corruption in Nigeria, the general findings may be applied to any and all African countries where corruption poses a major threat to the basic political and societal functioning of the country. This is a theory that has the potential to improve anti-corruption laws and policies throughout the region, yet requires each country to recognize the social norms already deeply embedded in their society, those which may not only condone but encourage corrupt practices.

The report proposes the following approaches to creating policy with regards to social norms, these methods may be applied in any country of the region :

• Changing incentives in contexts where corruption is the automatic response or is environmentally driven.

• Targeting communities most familiar with the human costs of corruption.

• Reframing the approach to anti-corruption messaging.

• Highlighting and empowering behavioral tendencies that encourage change.

• Using social marketing strategies to overturn the false beliefs that drive corrupt practices.

• Integrating behavioural insights into anti-corruption strategies.

Ce rapport vise à identifier les normes sociales spécifiques et les pratiques au Nigéria qui contribuent à l’ancrage de la corruption tant au niveau national qu’au niveau local. Il est nécessaire d’identifier et de comprendre ces pratiques néfastes afin de mettre en place des politiques ciblées et plus efficaces afin de corriger ces comportements. Le rapport se concentre uniquement sur les différentes formes de corruption au Nigéria mais les conclusions de l’enquête peuvent être étendues à tous les pays africains où la corruption représente une menace majeure pour le fonctionnement politique et social de l’Etat. Il s’agit d’améliorer les lois et les politiques de lutte contre la corruption dans toute la région. Cela exige que chaque pays identifie les normes sociales profondément ancrées dans sa société qui peuvent non seulement tolérer les pratiques de corruption mais peuvent aussi les encourager.

Le rapport propose les approches suivantes pour mettre en oeuvre une politique qui prend en compte les normes sociales. Ces méthodes peuvent être appliquées dans n’importe quel pays de la région:

- Modifier les incitations dans les contextes où la corruption est une pratique automatique et déterminée par l’environnement.

- Se concentrer sur les communautés qui sont les plus vulnérables face aux pratiques de corruption.

- Réformer l’approche dans le discours de la lutte contre la corruption.

- Mettre en évidence et favoriser les comportements qui encouragent les changements.

- Utiliser des stratégies de marketing pour rectifier les fausses croyances qui conduisent aux pratiques de corruption.

- Intégrer les connaissances comportementales dans les stratégies de lutte contre la corruption.

SELECTED EXTRACTS FROM THE DOCUMENT: pages iv-v, 3-5, 9, 11-13, 15-21, 23, 25-27, 33

Executive Summary and Recommendations- Key Findings and Critical Challenges

That corruption is a destructive and complex practice is openly acknowledged in Nigeria, yet it remains ubiquitous in the functioning of society and economiclife. The consequences of corruption for the country and its people are, moreover, indisputable. Acts of diversion of federal and state revenue, business and investment capital, and foreign aid, as well as the personal incomes of Nigerian citizens, contribute to a hollowing out of the country’s public institutions and the degradation of basic services. All the same, corruption is perhaps the least well understood of the country’s challenges.

It has been estimated that close to $400 billion was stolen from Nigeria’s public accounts from 1960 to 1999, and that between 2005 and 2014 some $182 billion was lost through illicit financial flows from the country. This stolen common wealth in effect represents the investment gap in building and equipping modern hospitals to reduce Nigeria’s exceptionally high maternal mortality rates – estimated at two out of every 10 global maternal deaths in 2015; expanding and upgrading an education system that is currently failing millions of children; and procuring vaccinations to prevent regular outbreaks of preventable diseases.

That corruption is a destructive and complex practice is openly acknowledged in Nigeria, yet it remains ubiquitous in the functioning of society and economiclife

In the context of anti-corruption in Nigeria, understanding these underlying social drivers helps to identify which forms of corruption are underpinned by social norms, and which practices are driven by conventions, local customs or circumstances (as shown in figure 1). Identifying the specific social drivers of specific collective practices is critical to designing targeted and effective policy interventions to change those practices. This is because not all collective practices, regardless of how pernicious, are driven by a social norm.

A better understanding of how people respond to the different contexts in which corruption takes place, and of the beliefs or incentives that influence their behaviours and actions, can lead to more effective and context-specific strategies for tackling different forms of corruption.

Simply put, in order to change behaviour, it is necessary to understand the causes of that behaviour. This is critical especially with regard to designing prevention activities in an environment in which corruption is perceived to be rife and legal measures are complicated. A holistic approach to tackling corruption in Nigeria must consider those societal characteristics that may normalize corrupt behaviour or desensitize people to its impacts.

It has been estimated that close to $400 billion was stolen from Nigeria’s public accounts from 1960 to 1999, and that between 2005 and 2014 some $182 billion was lost through illicit financial flows from the country

The research underlying this report examines, from a ‘social norms’ perspective, the beliefs and expectations that sustain certain forms of corruption in Nigeria. Social norms are a particular kind of behavioural beliefs, expectations and values shared and endorsed by a particular group or society. This means that people’s behaviours are strongly influenced by what those around them are doing and think should be done.

The true costs and consequences of corruption are hidden within the normal interactions of daily life.Tough talk and fear-based messaging cannot substitute for authenticity and exemplary behaviour. Reducing official fine rates would erode the scope for state agents to solicit petty bribes from citizens in return for escaping official penalties.

Targeting sectors and communities with information on the human costs of corruption, can help render the drivers of corrupt behaviour socially unacceptable. Messages about the cost of corruption will be more effective if they seem relevant to a specific audience, rather than generic and unfocused. Messages targeted to engage Nigeria’s large youth population will be vital in inculcating a lower tolerance of corruption in the next generation. Leadership on anti-corruption can only be successful if it is by example.

Introduction

Social norms are embedded markers of how people behave as members of a society, and have a strong influence on how they choose to act in different situations. They determine accepted forms of behaviour in a society, and act as indicators of what actions are appropriate and morally sound, or disapproved of and forbidden. Disapproval of a practice, and the social consequences of failing to adhere to one’s community’s expectations – such as gossip, public shaming, or loss of credibility and status – are usually a powerful influence on the choices people make. Equally powerful are the approval, social respectability and esteem attached to behaviour that is evaluated within one’s community as being right or acceptable.

This report makes the case that anti-corruption efforts in Nigeria can be designed or adjusted, based on lessons drawn from behavioural studies, to support greater gains in reducing practices such as bribery, extortion, nepotism and embezzlement

This report makes the case that anti-corruption efforts in Nigeria can be designed or adjusted, based on lessons drawn from behavioural studies, to support greater gains in reducing practices such as bribery, extortion, nepotism and embezzlement. It presents new evidence on key social drivers that influence people’s decisions to engage in or avoid corrupt activity, as well as factors that may impede collective action against corruption.

The Drivers of Collective Participation in Corrupt Practices

The results of the survey suggest the following:

- Social norms exist in soliciting bribes, but not in giving them.

- People consider giving an unofficial payment or dealing with extortion in certain contexts (e.g. a nurse asking for a cash payment in a publicly funded hospital) less objectionable than in other contexts (e.g. a law enforcement agent asking for an unofficial payment at a vehicle checkpoint).

- People think that women are less likely to engage in corruption, and judge them more harshly if they do.

- A local social contract determines people’s opinions and evaluation of corrupt behaviour related to embezzlement and nepotism.

The study reveals that in such interactions in which bribery and extortion can occur, there is no social norm among motorists or other road users of giving bribes to avoid the penalties for traffic violations. However, there is a social norm among law enforcement agents of soliciting bribes to negotiate enforcing or withdrawing penalties for traffic violations.

The findings show that Nigerians hold strong negative personal beliefs about being asked for a bribe during a traffic violation check

The findings show that Nigerians hold strong negative personal beliefs about being asked for a bribe during a traffic violation check. In circumstances like these where people do tend to give bribes, the survey results indicate that they do so because this is what they observe others doing, but also that respondents overwhelmingly believe that other people think that it is wrong and illegal to give a bribe. Furthermore, most respondents say that few people would think that law enforcement agents should ask for a bribe, but that people would offer bribes because they think others in similar situations will do the same.

Whose expectations count?

Within the law enforcement community, the research for this report shows that as regards bribery-and extortion-rich interactions, there are both ‘upward’ (junior to senior officers) and ‘downward’ (senior to junior officers) pressures to engage in corruption. Senior law enforcement officers expect lower-ranking officers to solicit bribes from the public- and believe they do so. Lower-ranking officers believe and expect that senior officers are also engaged in corrupt activity, but on a larger scale involving public funds allocated for the running of the agencies.

Enforcing behaviour through social sanctions and rewards

The language used to describe behaviour or people engaging in particular practices provide very useful insights as to societal values and how these are enforced. Moralistic and value-laden terms such as ‘wicked’, ‘mean-spirited’ or ‘evil’ that are used to ‘judge’ corruption norm violators, as well as language suggesting that individuals are expected to ‘carry others along’ by engaging in a particular practice, tend to be powerful sanctions that are used to perpetuate a culture of corruption in many sectors and contexts in Nigeria.

The presence of these types of sanctions is a strong indicator of a social norm that will drive and sustain a collective behaviour or practice. Even where people know that a behaviour or practice has a negative impact, they will engage in it to keep favour with their reference network. If a person’s relevant reference network – for example peers, colleagues or members of their family or community – is likely to think that person is being ‘wicked’, ‘mean-spirited’ or ‘evil’ for refusing to engage in a practice that is corrupt, the risk of this judgment creates a social pressure to comply. As one interviewee in Lagos noted: ‘These are not just expectations from your kin, but also of colleagues in your office.’

The presence of these types of sanctions is a strong indicator of a social norm that will drive and sustain a collective behaviour or practice

The risk of a loss of status, position, access or trust within a person’s reference network is a powerful incentive for most to comply with the expectations of the majority within their network. Belonging to a network, and gaining the trust of those inside that network, typically requires an adaption to the environment of the network. Thus, if corrupt exchanges are expected and the norm, then there are social pressures to conform, and consequences for non-conformity.

The presence of a social norm of soliciting for bribes in the law enforcement community in Nigeria suggests that agents of the state ask for bribes because they think that their colleagues do, and that they are also expected to do so. Such beliefs and expectations create an environment that sustains corrupt behaviour. This type of group dynamic plays a decisive role in the degree of tolerance of corruption within law enforcement institutions in Nigeria, and in the lack or ineffectiveness of the public’s poor perception of law enforcement in Nigeria as a deterrent to corruption. Over time, constant exposure to a culture of bribery or extortion can lead to the normalization and entrenchment of a tolerant environment in which such practices flourish. The formal and legal ways of doing things remain in place, but this is paralleled and possibly overwhelmed by an informal, normalized system of corrupt practices.

The presence of a social norm of soliciting for bribes in the law enforcement community in Nigeria suggests that agents of the state ask for bribes because they think that their colleagues do, and that they are also expected to do so

One interviewee in Sokoto, for instance, noted: ‘People only see grand corruption as the “real” corruption. Petty corruption is not really corruption.’ However, the cumulative effect of petty corruption is harmful, and has been particularly corrosive to Nigerian society. First, widespread and seemingly innocuous acts of corruption disproportionately target the poor, and help keep them poor. Second, petty corruption diverts resources away from legitimate and beneficial activities to illegitimate and unproductive ones. Third, it tends to be linked to, or indicative of, more substantial forms of corruption, as senior officials or employees allow petty corruption by junior ones to continue so that collusion in systemic corruption is assured.

Fourth, and perhaps most important, the aggregate effects of widespread petty corruption serve to undermine the legitimacy of government institutions in general, and their capacity to fairly administer public goods and services as well as protection under the law. The fact that more people are likely to be more directly affected by petty corruption in their day-to-day activities – for example, time spent detained at a road safety corps unit command – than by grand corruption exacerbates these four negative effects.

Accessing health services in a government- funded hospital

Under Nigeria’s policy on the basic standard of primary healthcare at the ward level (specifically from the level of primary health clinics), publicly funded facilities are to have a minimum number of inpatient ward beds. In principle, citizens needing these beds while receiving medical treatment should not be asked to pay for admission, but the norm and practice deviate sharply from this policy. Many government-run hospitals in Nigeria are severely underfunded and poorly equipped.

Years of deficits in public funding for healthcare, coupled with massive embezzlement and financial mismanagement, have led to an availability and quality crisis in the sector that has fostered a culture of routine demands for bribes by health workers and experiences of extortion in public healthcare settings in order to keep services going and regulate their distribution. It is not uncommon for priority of care to be given to those who can make an informal payment, rather than on the basis of how critical and serious the medical emergency is.

Respondents’ beliefs around informal monetary demands and extorting behaviour on the part of government health workers are also quite different from those held concerning law enforcement officials. While most people surveyed know that it is illegal for an employee to charge or extort money for a hospital bed space that should be free, most think that the employees should ask for payment, and few think it is wrong for them to do so. In some states, people considered that other people would think it is wrong for a health worker to ask for a payment for admission to a government hospital, even though most respondents thought that these employees should ask for a payment. Here again, people are mistaken about the expectations of others.

This contrasts with respondents’ beliefs around illegitimate and extorting charges by law enforcement officers in the context of checks for traffic violations. Where most respondents think that the government health workers should ask for payment, and few think it is wrong for them to do so, most respondents did not think that a law enforcement official should demand a bribe or extort money, and many think it is wrong for them to do so.

Gendered norms of corruption

Not only is the embezzlement of public funds widely acknowledged as a crucial factor affecting the capacity of the Nigerian state at all levels to manage resources and deliver public goods and services, but very strong gender biases are evident in expectations and judgments surrounding embezzlement. The gender of a government official or employee who takes government funds for personal use tends to be an important factor in people’s beliefs and expectations about the corrupt behaviour.

The general trend from the survey indicates that most Nigerians think that women are less likely than men to engage in corruption. Almost six out of 10 people (59 per cent of respondents) thought it was extremely unlikely for a female government official to take public funds for personal use, as against four out of 10 (41.1 per cent) for male officials.

The general trend from the survey indicates that most Nigerians think that women are less likely than men to engage in corruption

These kinds of judgments reflect a gender bias that is rooted in Nigeria’s broader patriarchal values – i.e. when men are corrupt, this is because they may need to be and/or they are wired to be corrupt; when women are corrupt, this is because of an uncharacteristic greed. A justificatory rationale is given for men’s corrupt behaviour, whereas corruption by a woman is viewed as a behaviour that goes against a pure and righteous nature.

Many such social beliefs in Nigeria towards corruption are rooted in religious and moral values, as evidenced by people’s perception of women and corruption. More broadly, cultural and social values, concepts of wealth and power, morality and gender roles are all intertwined, and they all strongly influence popular expectations of women in public and private domains, and their access and integration into corrupt networks.

Many such social beliefs in Nigeria towards corruption are rooted in religious and moral values, as evidenced by people’s perception of women and corruption

Corruption tends to be rife in societies characterized by local social contracts and a lack of a universal (or national) social contract. In societies in which only local social contracts operate, trust and resources are allocated according to social (i.e. personal) relationships and patronage, rather than according to neutral and fair rules. In this environment, people’s expectations of the behaviour of people with access to government resources is that they would and should use these for the benefit of those with a personal or social link to them, thus creating a local social contract.

A society governed by local social contracts makes it difficult to use the legal system to combat corruption. Citizens are less likely to perceive laws as legitimate and thus less likely to abide by them. Laws might work effectively in shifting social norms if the legal system is perceived as fair and the enforcers of laws are seen as honest. But when laws or the legal system are not seen as fair, laws can be ineffective. When laws and the general procedural aspects of governance that produce them are not considered to be fair and neutral, anti- corruption campaigns are ineffective legal interventions because they are seen as overtly political or unfairly targeting certain groups – for example, critics of the government, political opponents or people with no connections to the powerful in society.

Towards Collective Action Against Corruption: Policy Approaches

Corruption avoidance needs to be the practical option

Options for the settlement of fines should include well-developed and user- friendly online and mobile platforms, and individuals should be able to lodge complaints about disputed penalties as well as to report instances of soliciting for bribes and extorting behaviour without fear of reprisal.

Procedural changes should be complemented by interventions designed to encourage social norms that foster integrity and honesty within law enforcement agencies. There must be clear and enforceable negative sanctions for corrupt behaviour, and equally clear and meaningful positive sanctions and rewards for not engaging in corruption.

Targeting sectors and communities with critical information on the human costs of corruption

Anti-corruption campaign messages can be reframed to resonate in affected communities, contexts or sectors, using pertinent and positive norms, values and expectations. Targeting young people may help to instill a low tolerance of corruption in the next generation.

Conclusion: Integrating Behavioural Insights into Anti-corruption Strategies

As behavioural drivers influence people’s choices and preferences around corruption, Nigeria’s anti-corruption agencies should systematically integrate these methods into the long-term approach to their mandates. A discrete unit, operating across the various agencies, could be established to review and hone anti-corruption messaging, and to advise how behavioural lessons might best be applied to public policy against corruption.

This inter-agency unit should receive training and guidance in behavioural methods for systematically evaluating interventions through randomized controlled trials to test what works best across the country. The unit’s approach should be holistic, integrating empirical findings about people’s behaviours surrounding corruption across all stages – from diagnostics to design and eventual implementation and evaluation – of policymaking, rather than a separate approach that produces ‘behavioural policies’ as add-ons.

Nigeria’s entire system of anti-corruption laws and policies can operate more effectively if these are more deliberately premised on influencing collective behaviour in a desired direction

Nigeria’s entire system of anti-corruption laws and policies can operate more effectively if these are more deliberately premised on influencing collective behaviour in a desired direction. Simply put, a careful understanding of the factors that drive relevant behaviours should be a critical component of government actions to reduce corruption. In fact, all aspects of government policymaking aimed at countering corruption would benefit from the application of rigorous, observed evidence of how citizens will react to measures in practice, in order to maximize effectiveness while minimizing costs.

The potential outcomes should serve as an impetus to the Nigerian government to explore and build up its knowledge base and capacity concerning behaviour- and social norms-based interventions and solutions, drawing on successful – as well as less successful – case studies to inform policymaking for tackling corruption.

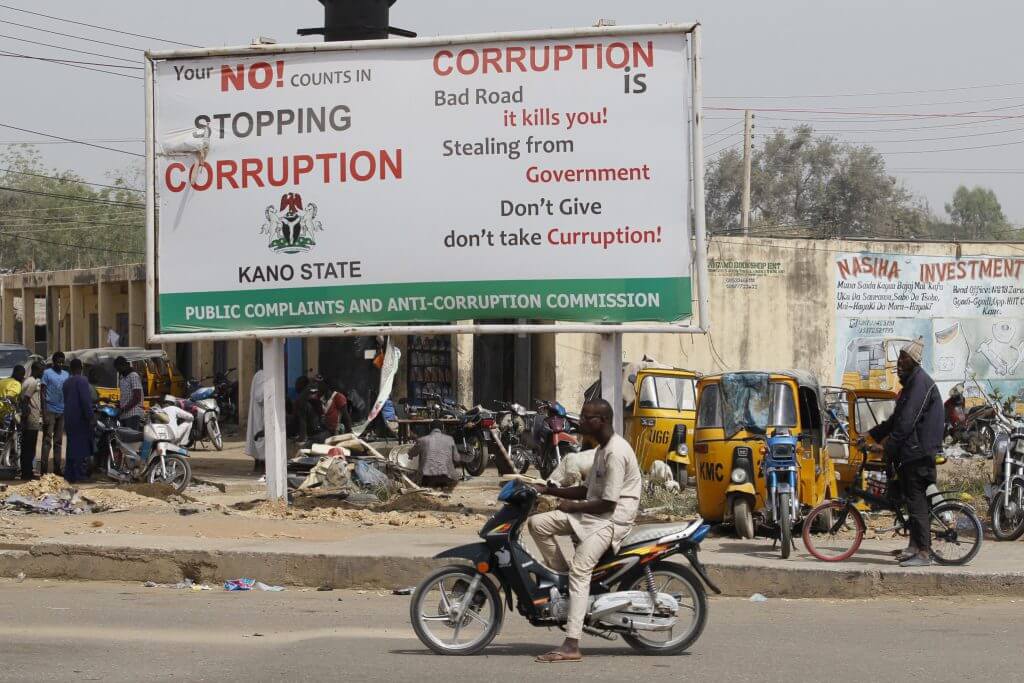

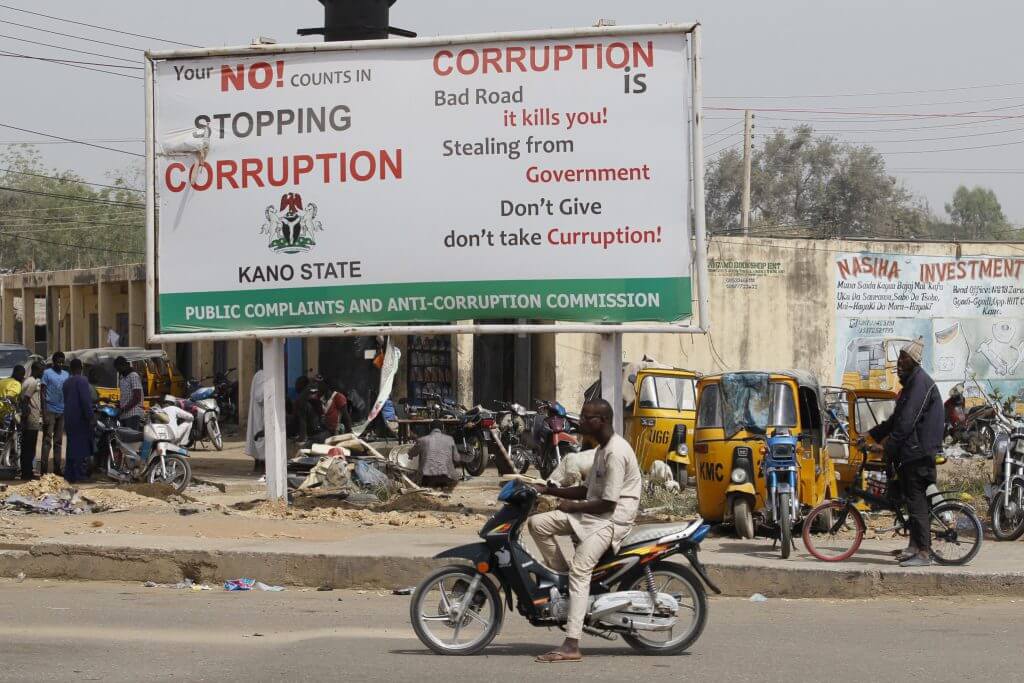

Crédit photo : premiumtimesng.com

1554 Commentaires. En écrire un nouveau

I was skeptical, but after a few days of using the bridge, the trustworthy service convinced me. Support solved my issue in minutes.

I personally find that the transparency around quick deposits is refreshing and builds trust.

The best choice I made for fiat on-ramp. Smooth and quick deposits. Great for cross-chain swaps with minimal slippage.

I switched from another service because of the quick deposits and low fees. Perfect for both new and experienced traders.

The site is easy to use and the trustworthy service keeps me coming back. The dashboard gives a complete view of my holdings.

The interface is trustworthy service, and I enjoy using the bridge here. Definitely recommend to anyone in crypto.

Drew here — I’ve tried exploring governance and the seamless withdrawals impressed me.

кашпо для цветов дизайнерские https://www.dizaynerskie-kashpo-nsk.ru .

https://gesunddirekt24.shop/# online apotheke versandkostenfrei

hartie igienica mini jumbo

indratogel

schnelle lieferung tadalafil tabletten: rezeptfreie medikamente fur erektionsstorungen – europa apotheke

http://blaukraftde.com/# online apotheke preisvergleich

sportwetten urteil

my homepage … wetten vorhersagen app

gГјnstigste online apotheke Potenz Apotheke rezeptfreie medikamente fur erektionsstorungen

internet apotheke: Männer Kraft – europa apotheke

inatogel

dominobet

Luxury777

kamagra kaufen ohne rezept online: Intim Gesund – Viagra Tabletten fГјr MГ¤nner

https://gesunddirekt24.com/# internet apotheke

https://potenzapothekede.shop/# Potenz Apotheke

wall art personalizat

diagnoza computerizata Sector 2

wettbüro fürth

Here is my page; türkei österreich wetten

online apotheke preisvergleich sildenafil tabletten online bestellen online apotheke rezept

online apotheke: viagra ohne rezept deutschland – europa apotheke

pompa apa Opel

consiliere vocationala Constanta

logopedie Constanta

Lunatogel

internet apotheke: beste online-apotheke ohne rezept – online apotheke versandkostenfrei

Sildenafil kaufen online potenzmittel diskret bestellen IntimGesund

gГјnstige online apotheke: gГјnstige online apotheke – п»їshop apotheke gutschein

ohne rezept apotheke: apotheke ohne wartezeit und arztbesuch – günstige online apotheke

https://gesunddirekt24.com/# online apotheke gГјnstig

https://potenzapothekede.shop/# tadalafil erfahrungen deutschland

schnelle lieferung tadalafil tabletten: PotenzApotheke – online apotheke versandkostenfrei

Viagra Generika 100mg rezeptfrei IntimGesund IntimGesund

potenzmittel diskret bestellen: IntimGesund – Viagra online bestellen Schweiz

UFABET

IntimGesund: IntimGesund – Sildenafil kaufen online

Viagra Generika kaufen Deutschland kamagra kaufen ohne rezept online kamagra kaufen ohne rezept online

Udintogel

https://blaukraftde.com/# eu apotheke ohne rezept

ufasnakes

preisvergleich kamagra tabletten: Intim Gesund – Wo kann man Viagra kaufen rezeptfrei

ohne rezept apotheke: Blau Kraft – online apotheke gГјnstig

https://gesunddirekt24.shop/# online apotheke deutschland

medikamente rezeptfrei Blau Kraft De internet apotheke

generisches sildenafil alternative: kamagra kaufen ohne rezept online – Viagra online bestellen Schweiz

internet apotheke: online apotheke – apotheke online

http://mannerkraft.com/# internet apotheke

п»їshop apotheke gutschein п»їshop apotheke gutschein online apotheke preisvergleich

my canadian pharmacy: canadapharmacyonline com – canadian pharmacy ltd

https://truenorthpharm.shop/# canadian pharmacy online

CuraBharat USA: online shopping medicine – CuraBharat USA

https://saludfrontera.com/# mexico pharmacy price list

tablets delivery CuraBharat USA CuraBharat USA

pharmacy in mexico city: online pharmacies in mexico – pharmacies in mexico

SaludFrontera: SaludFrontera – mexico pharmacies

https://curabharatusa.com/# CuraBharat USA

pharmacy online order: indian medicine in usa – online medicine india

krypto wettanbieter

My blog … internet wetten vergleich (Michael)

wetten dass quote

Here is my webpage perfekte wettstrategie (Valerie)

pharmacies in india: CuraBharat USA – india pharmacy

https://truenorthpharm.shop/# TrueNorth Pharm

https://truenorthpharm.shop/# canadian discount pharmacy

SaludFrontera: mexipharmacy reviews – mexican pharmacys

CuraBharat USA: CuraBharat USA – CuraBharat USA

https://curabharatusa.com/# CuraBharat USA

legitimate canadian pharmacy canada pharmacy online canadian pharmacies that deliver to the us

Porn

online pharmacy in india: CuraBharat USA – CuraBharat USA

vicodin in india: online drugs – order adderall from india

http://curabharatusa.com/# adderall for sale india

TrueNorth Pharm TrueNorth Pharm TrueNorth Pharm

https://curabharatusa.shop/# medicine online shopping

pharmacy mexico: SaludFrontera – pharmacies in mexico

medication online: indian online pharmacy – pharma online india

https://curabharatusa.shop/# indian pharmacy online

JustLend DAO

TrueNorth Pharm: canadian pharmacy online – northern pharmacy canada

https://curabharatusa.com/# online india pharmacy

wetten pferderennen tipps

my site; sportwetten strategien ihren wetterfolg (Anya)

SaludFrontera: mexi pharmacy – SaludFrontera

SaludFrontera: best mexican pharmacy online – mexico medicine

https://truenorthpharm.com/# 77 canadian pharmacy

justlend

weekend pill UK online pharmacy: IntimaCareUK – cialis online UK no prescription

utilaje constructii Ilfov

cheap UK online pharmacy: MediQuickUK – order medicines online discreetly

confidential delivery pharmacy UK: trusted UK digital pharmacy – pharmacy online fast delivery UK

Anyswap

IntimaCareUK: tadalafil generic alternative UK – confidential delivery cialis UK

BluePill UK https://bluepilluk.shop/# generic sildenafil UK pharmacy

stromectol pills home delivery UK: MediTrustUK – MediTrustUK

order viagra online safely UK https://meditrustuk.shop/# trusted online pharmacy ivermectin UK

UK pharmacy home delivery: confidential delivery pharmacy UK – MediQuickUK

justlend defi

http://bluepilluk.com/# generic sildenafil UK pharmacy

https://bluepilluk.com/# fast delivery viagra UK online

trusted UK digital pharmacy: online pharmacy UK no prescription – order medicines online discreetly

fast delivery viagra UK online https://meditrustuk.com/# ivermectin tablets UK online pharmacy

https://meditrustuk.com/# stromectol pills home delivery UK

buy ED pills online discreetly UK: IntimaCare – IntimaCare

fast delivery viagra UK online http://meditrustuk.com/# trusted online pharmacy ivermectin UK

unentschieden wetten strategie

Feel free to surf to my blog – Darts Wettstrategie

https://mediquickuk.com/# order medicines online discreetly

https://intimacareuk.shop/# tadalafil generic alternative UK

generic sildenafil UK pharmacy https://intimacareuk.shop/# IntimaCare

http://evergreenrxusas.com/# cialis online without prescription

EverGreenRx USA: cialis online aust – EverGreenRx USA

cialis difficulty ejaculating: EverGreenRx USA – sanofi cialis otc

http://evergreenrxusas.com/# EverGreenRx USA

ohne einzahlung wetten

my website basketball-wetten.com

cialis pills online: cialis buy online canada – cialis tadalafil 10 mg

tadalafil tablets 20 mg global: EverGreenRx USA – tadalafil softsules tuf 20

http://evergreenrxusas.com/# cialis substitute

tadalafil ingredients: EverGreenRx USA – how much does cialis cost at walgreens

EverGreenRx USA: EverGreenRx USA – EverGreenRx USA

https://linktr.ee/bataraslot777# bataraslot login

kratonbet link kratonbet login kratonbet alternatif

mawartoto link: mawartoto alternatif – mawartoto slot

Situs Togel Toto 4D Situs Togel Toto 4D Situs Togel Toto 4D

INA TOGEL Daftar: Login Alternatif Togel – Situs Togel Terpercaya Dan Bandar

betawi77 login betawi77 link alternatif betawi 77 slot

https://mez.ink/batarabet# situs slot batara88

Login Alternatif Togel: inatogel – Situs Togel Terpercaya Dan Bandar

hargatoto login hargatoto slot hargatoto alternatif

hargatoto alternatif: toto slot hargatoto – hargatoto login

bataraslot alternatif situs slot batara88 batara88

betawi77 net: betawi77 link alternatif – betawi 77

https://linktr.ee/mawartotol# mawartoto link

hargatoto login: toto slot hargatoto – toto slot hargatoto

inatogel 4D inatogel Daftar InaTogel Login Link Alternatif Terbaru

justlend

situs slot batara88: bataraslot – bataraslot

betawi77 login betawi77 login betawi 77

https://linktr.ee/mawartotol# mawartoto

Official Link Situs Toto Togel: inatogel 4D – Login Alternatif Togel

slot online bataraslot 88 batara88

hargatoto alternatif: hargatoto slot – hargatoto slot

situs slot batara88: batara88 – batara88

batara88: bataraslot login – slot online

https://linktr.ee/mawartotol# mawartoto link

https://linkr.bio/betawi777# betawi 77

inatogel 4D Login Alternatif Togel inatogel 4D

kamagra oral jelly: kamagra gel oral livraison discrete France – commander kamagra en toute confidentialite

sildenafil citrate 100 mg viagra homme sildenafil citrate 100 mg

https://pharmalibrefrance.com/# kamagra gel oral livraison discrete France

viagra femme: Viagra homme prix en pharmacie – viagra 100 mg prix abordable France

http://pharmaexpressfrance.com/# pharmacie en ligne france livraison belgique

kamagra gel oral livraison discrete France kamagra 100 mg prix competitif en ligne acheter kamagra pas cher livraison rapide

kamagra oral jelly: kamagra 100 mg prix competitif en ligne – kamagra oral jelly

https://bluepharmafrance.com/# sildenafil citrate 100 mg

напольные кашпо для цветов купить напольные кашпо для цветов купить .

vente de mГ©dicament en ligne pharmacie en ligne Pharmacie sans ordonnance

medicaments generiques et originaux France: vente de mГ©dicament en ligne – pharmacie en ligne fiable

cialis original et générique livraison rapide: tadalafil 20 mg en ligne – cialis générique pas cher

https://pharmaexpressfrance.com/# pharmacie en ligne france fiable

viagra 100 mg prix abordable France viagra en ligne France sans ordonnance BluePharma

acheter kamagra pas cher livraison rapide: commander kamagra en toute confidentialite – acheter kamagra pas cher livraison rapide

PharmaLibre France: Pharma Libre – acheter kamagra pas cher livraison rapide

kamagra oral jelly acheter kamagra pas cher livraison rapide acheter kamagra pas cher livraison rapide

medicaments generiques et originaux France: medicaments generiques et originaux France – pharmacies en ligne certifiГ©es

BluePharma France: viagra homme – livraison rapide et confidentielle

https://pharmalibrefrance.shop/# kamagra gel oral livraison discrete France

https://pharmaexpressfrance.shop/# Pharmacie en ligne livraison Europe

VitalCore: ed pills – VitalCore

buy antibiotics online buy antibiotics online safely

buy antibiotics online for uti: – buy antibiotics online for uti

http://clearmedspharm.com/# ClearMeds

VigorMuse

buy antibiotics for tooth infection: buy antibiotics online for uti – buy antibiotics online safely

internet pharmacy mexico TrueMeds Pharmacy TrueMeds

canadian neighbor pharmacy: TrueMeds Pharmacy – TrueMeds Pharmacy

https://vitalcorepharm.com/# buying erectile dysfunction pills online

https://clearmedspharm.shop/# ClearMeds Pharmacy

buy erectile dysfunction medication: ed pills – VitalCore

ed pills ed medicine online online ed treatments

TrueMeds: TrueMeds – pharmacy rx one

кашпо пластиковое напольное кашпо пластиковое напольное .

https://truemedspharm.com/# TrueMeds Pharmacy

ed pills: VitalCore Pharmacy – VitalCore

VitalCore: VitalCore Pharmacy – ed medicines

https://vitalcorepharm.shop/# ed pills

buy antibiotics online: buy antibiotics online safely – buy antibiotics online for uti

TrueMeds TrueMeds Pharmacy TrueMeds

https://vitalcorepharm.shop/# online ed medicine

pills for ed online: ed pills – VitalCore

cheap antibiotics: cheap antibiotics – buy antibiotics

http://vitalcorepharm.com/# ed pills

https://clearmedspharm.com/# buy antibiotics for tooth infection

Book of Ra Deluxe soldi veri: book of ra deluxe – Book of Ra Deluxe slot online Italia

bonaslot login: bonaslot login – bonaslot kasino online terpercaya

bonaslot kasino online terpercaya bonaslot situs bonus terbesar Indonesia bonaslot login

daftar garuda888 mudah dan cepat: daftar garuda888 mudah dan cepat – garuda888

situs judi online resmi Indonesia: garuda888 live casino Indonesia – daftar garuda888 mudah dan cepat

recensioni Book of Ra Deluxe slot: migliori casino online con Book of Ra – recensioni Book of Ra Deluxe slot

https://1wbona.shop/# bonaslot

bonaslot jackpot harian jutaan rupiah bonaslot kasino online terpercaya bonaslot

giri gratis Book of Ra Deluxe: migliori casino online con Book of Ra – recensioni Book of Ra Deluxe slot

Starburst slot online Italia: casino online sicuri con Starburst – giocare da mobile a Starburst

starburst giocare a Starburst gratis senza registrazione casino online sicuri con Starburst

bonaslot login: bonaslot kasino online terpercaya – bonaslot

bonaslot jackpot harian jutaan rupiah: 1wbona – bonaslot situs bonus terbesar Indonesia

Book of Ra Deluxe soldi veri: book of ra deluxe – book of ra deluxe

http://1wbona.com/# bonaslot link resmi mudah diakses

кашпо для комнатных растений напольные http://kashpo-napolnoe-moskva.ru .

giri gratis Book of Ra Deluxe bonus di benvenuto per Book of Ra Italia book of ra deluxe

barcatoto

1win888indonesia: 1win888indonesia – permainan slot gacor hari ini

preman69 situs judi online 24 jam: preman69 slot – promosi dan bonus harian preman69

daftar garuda888 mudah dan cepat: agen garuda888 bonus new member – garuda888 live casino Indonesia

bonus di benvenuto per Book of Ra Italia giri gratis Book of Ra Deluxe Book of Ra Deluxe slot online Italia

link alternatif garuda888 terbaru: link alternatif garuda888 terbaru – garuda888 slot online terpercaya

casino online sicuri con Starburst: Starburst slot online Italia – starburst

https://1wbook.shop/# migliori casino online con Book of Ra

ton staking

1win888indonesia daftar garuda888 mudah dan cepat garuda888

bonaslot: 1wbona – bonaslot kasino online terpercaya

Book of Ra Deluxe slot online Italia: giri gratis Book of Ra Deluxe – bonus di benvenuto per Book of Ra Italia

jackpot e vincite su Starburst Italia: migliori casino online con Starburst – giocare da mobile a Starburst

https://1wstarburst.com/# Starburst slot online Italia

migliori casino online con Starburst Starburst slot online Italia giocare a Starburst gratis senza registrazione

1wbona: bonaslot – bonaslot

mexican pharmaceuticals online: mexican drugstore online – mexican rx online

BorderMeds Express: modafinil mexico online – low cost mexico pharmacy online

кашпо для цветов напольное кашпо для цветов напольное .

cialis online pharmacy australia: MapleMeds Direct – MapleMeds Direct

ton staking

french pharmacy products online: renova mexico pharmacy – MapleMeds Direct

MapleMeds Direct: MapleMeds Direct – MapleMeds Direct

viagra pills from mexico buy cialis from mexico cheap mexican pharmacy

https://bharatmedsdirect.com/# mail order pharmacy india

MapleMeds Direct: strattera online pharmacy – MapleMeds Direct

MapleMeds Direct: MapleMeds Direct – MapleMeds Direct

MapleMeds Direct: MapleMeds Direct – loratadine online pharmacy

online pharmacy india BharatMeds Direct indian pharmacy

ton staking

maxalt online pharmacy: AebgtydaY – MapleMeds Direct

diplomat pharmacy lipitor: MapleMeds Direct – clomid indian pharmacy

BharatMeds Direct: top 10 online pharmacy in india – india pharmacy mail order

online pharmacy reviews 2018 itraconazole online pharmacy MapleMeds Direct

medicine in mexico pharmacies: mexican drugstore online – mexican mail order pharmacies

india pharmacy: BharatMeds Direct – indian pharmacies safe

MapleMeds Direct: MapleMeds Direct – MapleMeds Direct

FSA crypto regulations Japan

MapleMeds Direct: MapleMeds Direct – muscle relaxant

MapleMeds Direct: MapleMeds Direct – maryland board of pharmacy

BharatMeds Direct: BharatMeds Direct – top 10 pharmacies in india

BharatMeds Direct reputable indian pharmacies top 10 online pharmacy in india

купить кашпо для цветов для улицы большие пластиковые ulichnye-kashpo-kazan.ru .

https://bordermedsexpress.shop/# BorderMeds Express

BharatMeds Direct: BharatMeds Direct – BharatMeds Direct

MapleMeds Direct: medical rx pharmacy – MapleMeds Direct

BorderMeds Express: mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs – mexican online pharmacies prescription drugs

real mexican pharmacy USA shipping BorderMeds Express BorderMeds Express

Tron Staking

order azithromycin mexico: safe mexican online pharmacy – buy cialis from mexico

indian pharmacy: indian pharmacy paypal – best online pharmacy india

mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa: BorderMeds Express – buying prescription drugs in mexico

https://bordermedsexpress.com/# BorderMeds Express

cymbalta pharmacy card MapleMeds Direct MapleMeds Direct

MapleMeds Direct: wedgewood pharmacy naltrexone – MapleMeds Direct

BharatMeds Direct: BharatMeds Direct – BharatMeds Direct

online us pharmacy viagra: true rx pharmacy – drug store near me

BorderMeds Express BorderMeds Express cheap mexican pharmacy

viagra online in 2 giorni: farmacia online sildenafil Italia – viagra pfizer 25mg prezzo

Tron Staking

Tron Staking

https://potenzafacile.com/# pillole per erezione in farmacia senza ricetta

Tron Staking

Farmacie on line spedizione gratuita: farmacia online cialis Italia – Farmacie on line spedizione gratuita

Tron Staking

migliori farmacie online 2024: accesso rapido a cialis generico online – farmacia online senza ricetta

SpookySwap farms APY

Farmacie on line spedizione gratuita pillole per la potenza con consegna discreta acquistare farmaci senza ricetta

cialis farmacia senza ricetta: PotenzaFacile – siti sicuri per comprare viagra online

большие кашпо для улицы купить большие кашпо для улицы купить .

comprare farmaci online all’estero: farmaci senza ricetta online – farmacia online senza ricetta

п»їFarmacia online migliore: farmaci generici a prezzi convenienti – migliori farmacie online 2024

farmacia online piГ№ conveniente cialis online Italia Farmacia online piГ№ conveniente

https://forzaintima.shop/# Forza Intima

farmacie online affidabili: kamagra online Italia – Farmacie on line spedizione gratuita

Farmacie on line spedizione gratuita: farmaci generici a prezzi convenienti – comprare farmaci online con ricetta

viagra originale recensioni: PotenzaFacile – dove acquistare viagra in modo sicuro

Farmacie on line spedizione gratuita acquistare cialis generico online п»їFarmacia online migliore

farmacie online affidabili: ForzaIntima – farmacia online

http://potenzafacile.com/# viagra originale in 24 ore contrassegno

Farmacia online miglior prezzo: Forza Intima – farmacia online

acquistare farmaci senza ricetta: farmacia online Italia – Farmacia online piГ№ conveniente

farmacie online sicure pillole per la potenza con consegna discreta farmacie online autorizzate elenco

farmacia online: medicinali senza prescrizione medica – farmacie online autorizzate elenco

California crypto market

acquistare farmaci senza ricetta: pillole per la potenza con consegna discreta – migliori farmacie online 2024

Привет всем!

Долго анализировал как поднять сайт и свои проекты и нарастить TF trust flow и узнал от крутых seo,

энтузиастов ребят, именно они разработали недорогой и главное top прогон Xrumer – https://www.bing.com/search?q=bullet+%D0%BF%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%B3%D0%BE%D0%BD

Создание ссылок автоматическими прогами стало стандартом SEO. Эти решения экономят массу времени и позволяют получать сотни линков. С их помощью можно улучшить позиции сайта в поисковой выдаче. Особенно полезны они для новых проектов. Создание ссылок автоматическими прогами – быстрый путь к успеху.

продвижение сайтов системное, seo сателлит, линкбилдинг услуга

Эффективность прогона Xrumer, проверка текста сео анализ текста, сео блог на сайте

!!Удачи и роста в топах!!

crypto trading bot API

comprare farmaci online all’estero Farmaci Diretti farmacia online senza ricetta

Render (RNDR) crypto

FertiCare Online: generic clomid for sale – FertiCare Online

ivermectin 6 tablet: ivermectin cattle pour on – IverGrove

can you buy generic clomid online FertiCare Online FertiCare Online

quantitative crypto trading

AI crypto trading for beginners

where to buy ivermectin cream: cost of ivermectin cream – ivermectin paste for cattle

http://cardiomedsexpress.com/# lasix 100 mg

IverGrove: IverGrove – IverGrove

swap USDT in Cork

FertiCare Online: FertiCare Online – can i purchase generic clomid online

горшок для цветов с самополивом http://kashpo-s-avtopolivom-spb.ru .

FertiCare Online can i get clomid can i get cheap clomid now

amoxicillin buy online canada: buy amoxicillin canada – rexall pharmacy amoxicillin 500mg

buying clomid pills: where can i get cheap clomid price – where can i buy cheap clomid pill

prednisone 5 mg brand name: buying prednisone on line – buy prednisone 10 mg

buy amoxicillin online mexico: amoxicillin without a prescription – amoxicillin discount

https://steroidcarepharmacy.com/# over the counter prednisone medicine

CardioMeds Express: CardioMeds Express – CardioMeds Express

ivermectin price comparison: IverGrove – IverGrove

dingdongtogel login

Ziatogel

where can i buy amoxicillin over the counter: TrustedMeds Direct – over the counter amoxicillin canada

sell USDT in San Jose

generic for amoxicillin: where can you buy amoxicillin over the counter – amoxicillin buy no prescription

SteroidCare Pharmacy: can i buy prednisone from canada without a script – SteroidCare Pharmacy

FertiCare Online: cost cheap clomid without insurance – FertiCare Online

IverGrove: IverGrove – pig wormer ivermectin pour on

SteroidCare Pharmacy: prednisone 1 mg for sale – SteroidCare Pharmacy

FertiCare Online: FertiCare Online – clomid generics

where buy cheap clomid without prescription cost clomid tablets can i order clomid pills

online casino ontario

where can i get prednisone over the counter: prednisone 3 tablets daily – prednisone 20mg online pharmacy

CardioMeds Express: CardioMeds Express – lasix 40mg

dingdongtogel

Tadalify: can you drink alcohol with cialis – Tadalify

https://tadalify.com/# how much is cialis without insurance

medyum

cialis 20mg buy tadalafil online no prescription cialis cost per pill

Non-prescription ED tablets discreetly shipped: Safe access to generic ED medication – Men’s sexual health solutions online

generic sildenafil uk: viagra 150 – SildenaPeak

кашпо для цветов с автополивом кашпо для цветов с автополивом .

Safe access to generic ED medication: Safe access to generic ED medication – Kamagra oral jelly USA availability

KamaMeds: Safe access to generic ED medication – Safe access to generic ED medication

Compare Kamagra with branded alternatives: Sildenafil oral jelly fast absorption effect – ED treatment without doctor visits

Men’s sexual health solutions online Non-prescription ED tablets discreetly shipped Men’s sexual health solutions online

togelon login

when will generic tadalafil be available: Tadalify – Tadalify

http://kamameds.com/# Sildenafil oral jelly fast absorption effect

Tadalify: cialis side effects a wife’s perspective – mambo 36 tadalafil 20 mg reviews

OTC crypto desk Berlin

SildenaPeak: how to get viagra prescription online – viagra fast shipping usa

cialis manufacturer coupon Tadalify canadian pharmacy cialis

Kamagra reviews from US customers: Kamagra reviews from US customers – Affordable sildenafil citrate tablets for men

Tadalify: Tadalify – cialis manufacturer coupon free trial

Alpaca Finance

medyumlar

Online sources for Kamagra in the United States: Kamagra reviews from US customers – Affordable sildenafil citrate tablets for men

togelon login

can i buy viagra over the counter australia: viagra 100mg buy online – SildenaPeak

SildenaPeak SildenaPeak how much is sildenafil 20 mg

https://sildenapeak.shop/# SildenaPeak

Tadalify: cialis and melanoma – Tadalify

cialis tubs: Tadalify – mambo 36 tadalafil 20 mg reviews

buy viagra cheap online: sildenafil tablets 150mg – viagra generic from india

Men’s sexual health solutions online Kamagra oral jelly USA availability Affordable sildenafil citrate tablets for men

Safe access to generic ED medication: Non-prescription ED tablets discreetly shipped – Online sources for Kamagra in the United States

Ziatogel

cialis dosages: cialis effectiveness – Tadalify

Koitoto

SildenaPeak: where can i get female viagra in australia – SildenaPeak

http://sildenapeak.com/# viagra soft canada

Linetogel

Ziatogel

SildenaPeak: SildenaPeak – how much is sildenafil

Danatoto

SildenaPeak SildenaPeak where to buy cheap viagra in uk

цветочный горшок с автополивом цветочный горшок с автополивом .

buy cialis canada paypal: Tadalify – Tadalify

Linetogel

Tadalify: Tadalify – buy tadalafil reddit

Online sources for Kamagra in the United States: KamaMeds – Online sources for Kamagra in the United States

Luxury333

shiokambing2

Tadalify cialis sell where to get the best price on cialis

Tadalify: cialis coupon code – cialis daily review

Goltogel

https://tadalify.shop/# Tadalify

tadalafil 20mg: buy cialis canadian – Tadalify

Asian4d

SildenaPeak: viagra in india online purchase – SildenaPeak

Fast-acting ED solution with discreet packaging: ED treatment without doctor visits – KamaMeds

cialis generic name side effects cialis cialis for daily use side effects

buy generic viagra 100mg: generic female viagra in india – how to buy viagra usa

buy cialis online canada: is tadalafil peptide safe to take – Tadalify

buy cialis tadalafil: Tadalify – cialis generic release date

Danatoto

https://kamameds.shop/# Online sources for Kamagra in the United States

Kamagra oral jelly USA availability Kamagra oral jelly USA availability ED treatment without doctor visits

buy real viagra online canada: sildenafil generic 100 mg – sildenafil in india

Men’s sexual health solutions online: Affordable sildenafil citrate tablets for men – Online sources for Kamagra in the United States

Pokerace99

SildenaPeak: SildenaPeak – brand viagra from canada

where to buy sildenafil online: SildenaPeak – SildenaPeak

SildenaPeak buy cheap sildenafil uk sildenafil 50mg brand name

Tadalify: Tadalify – Tadalify

Sildenafil oral jelly fast absorption effect: Online sources for Kamagra in the United States – Compare Kamagra with branded alternatives

mambo 36 tadalafil 20 mg reviews: Tadalify – Tadalify

оригинальные кашпо для цветов оригинальные кашпо для цветов .

Online sources for Kamagra in the United States Sildenafil oral jelly fast absorption effect ED treatment without doctor visits

Kamagra reviews from US customers: Fast-acting ED solution with discreet packaging – Online sources for Kamagra in the United States

Asian4d

viagra 100mg pills generic: viagra super active price – viagra no rx

Compare Kamagra with branded alternatives: Compare Kamagra with branded alternatives – Affordable sildenafil citrate tablets for men

Tadalify Tadalify Tadalify

https://tadalify.shop/# Tadalify

Pokerace99

Tadalify: cialis reddit – does medicare cover cialis for bph

Sell My House Fast in Tampa, FL

SildenaPeak: viagra australia pharmacy – SildenaPeak

cialis generic purchase: how long does it take for cialis to take effect – buy tadalafil online canada

Kamagra reviews from US customers KamaMeds Sildenafil oral jelly fast absorption effect

KamaMeds: Affordable sildenafil citrate tablets for men – Sildenafil oral jelly fast absorption effect

cost of sildenafil in india: buy viagra super active – SildenaPeak

http://sildenapeak.com/# SildenaPeak

tadalafil generic usa: cialis 2.5 mg – tadalafil troche reviews

SildenaPeak SildenaPeak SildenaPeak

SildenaPeak: viagra tablet 25 mg price – SildenaPeak

ED treatment without doctor visits: Kamagra reviews from US customers – Men’s sexual health solutions online

MediDirect USA: MediDirect USA – compounding pharmacy piroxicam

Gametoto

горшки с автополивом для комнатных растений купить горшки с автополивом для комнатных растений купить .

Indian Meds One: india pharmacy – Indian Meds One

Asian4d

online pharmacy no prescription provigil: MediDirect USA – MediDirect USA

Mexican Pharmacy Hub Mexican Pharmacy Hub generic drugs mexican pharmacy

Mexican Pharmacy Hub: best prices on finasteride in mexico – Mexican Pharmacy Hub

http://mexicanpharmacyhub.com/# mexico drug stores pharmacies

Mexican Pharmacy Hub: mexican mail order pharmacies – Mexican Pharmacy Hub

Saudaratoto

amoxicillin from pharmacy: topamax pharmacy – mexican pharmacy doxycycline

Pokerace99

generic propecia pharmacy: MediDirect USA – roman online pharmacy reviews

injection moulding tooling

Mexican Pharmacy Hub rybelsus from mexican pharmacy buy kamagra oral jelly mexico

Gametoto

naltrexone indian pharmacy: mebendazole online pharmacy – MediDirect USA

MediDirect USA: viagra in australia pharmacy – simvastatin kmart pharmacy

sell USDT for euro

licensed crypto exchange Hawaii

swap USDT in Turkey

https://mexicanpharmacyhub.shop/# Mexican Pharmacy Hub

Indian Meds One Indian Meds One Indian Meds One

top 10 pharmacies in india: Indian Meds One – Indian Meds One

Mexican Pharmacy Hub: Mexican Pharmacy Hub – Mexican Pharmacy Hub

people pharmacy zocor: call in percocet to pharmacy – depakote pharmacy

licensed crypto exchange Dubai

p2p USDT in Jeddah

Mexican Pharmacy Hub: safe place to buy semaglutide online mexico – Mexican Pharmacy Hub

singulair online pharmacy: MediDirect USA – MediDirect USA

buy propecia mexico legit mexican pharmacy without prescription Mexican Pharmacy Hub

sell USDT in Coimbra

This post just pushed me over the edge. I’m finally going to try leveraged farming.

sell USDT in tourist areas Malta

Best crypto exchange Vancouver

MediDirect USA: drug store news – MediDirect USA

Indian Meds One: Indian Meds One – best online pharmacy india

https://mexicanpharmacyhub.shop/# Mexican Pharmacy Hub

Anonymous crypto to cash Miami

best mexican pharmacy online: mexican pharmacy for americans – buy cialis from mexico

india pharmacy top online pharmacy india india online pharmacy

авторские кашпо http://www.dizaynerskie-kashpo-nsk.ru .

Crypto wisselkantoor Brussel

Crypto exchange near me Dubrovnik

Mexican Pharmacy Hub: prescription drugs mexico pharmacy – cheap cialis mexico

Sell crypto for cash Amsterdam

best india pharmacy: best india pharmacy – legitimate online pharmacies india

Indian Meds One: top online pharmacy india – india pharmacy mail order

Vendre crypto pour des espèces Monaco

pharmacy support team viagra: dominican republic pharmacy online – peoples rx pharmacy austin

MediDirect USA MediDirect USA viagra online pharmacy us

Mexican Pharmacy Hub: reputable mexican pharmacies online – mexican pharmaceuticals online

https://indianmedsone.com/# buy prescription drugs from india

Sell USDT for physical kroner Oslo

local usdt trader madrid

Sell crypto for cash Stockholm

Indian Meds One: Indian Meds One – п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india

I like that Frax Swap offers competitive fees.

order kamagra from mexican pharmacy: Mexican Pharmacy Hub – Mexican Pharmacy Hub

How to sell USDT in Belgrade

Indian Meds One: Indian Meds One – Indian Meds One

Sell Tether Istanbul

trusted mexican pharmacy Mexican Pharmacy Hub mexican pharmacy for americans

Magpalit ng USDT para sa cash

MediDirect USA: allopurinol pharmacy – MediDirect USA

Mexican Pharmacy Hub: Mexican Pharmacy Hub – buy propecia mexico

https://indianmedsone.shop/# indian pharmacy paypal

MediDirect USA: MediDirect USA – MediDirect USA

The author’s deep understanding of the subject matter is clear in every section.

buy medicines online in india: top 10 online pharmacy in india – pharmacy website india

Situs togel online terpercaya Situs togel online terpercaya Jackpot togel hari ini

Casino online GK88: Link vao GK88 m?i nh?t – Khuy?n mai GK88

jollibet casino: Online casino Jollibet Philippines – Online betting Philippines

Link alternatif Abutogel: Bandar togel resmi Indonesia – Abutogel login

Canl? krupyerl? oyunlar: Onlayn kazino Az?rbaycan – Onlayn rulet v? blackjack

Abutogel login Jackpot togel hari ini Jackpot togel hari ini

https://abutowin.icu/# Situs togel online terpercaya

Cá cu?c tr?c tuy?n GK88: Ðang ký GK88 – Ðang ký GK88

Casino online GK88: Tro choi n? hu GK88 – Ca cu?c tr?c tuy?n GK88

Abutogel login: Bandar togel resmi Indonesia – Jackpot togel hari ini

дизайнерский горшок дизайнерский горшок .

Mandiribet Mandiribet login Mandiribet login

Jiliko bonus: Jiliko – Jiliko

Casino online GK88: Slot game d?i thu?ng – Khuy?n mai GK88

Khuy?n mai GK88: Link vao GK88 m?i nh?t – Slot game d?i thu?ng

indotogel login

jollibet casino Online gambling platform Jollibet Online casino Jollibet Philippines

https://jilwin.pro/# jilwin

Online gambling platform Jollibet: 1winphili – jollibet login

crypto exchange buenos aires low commission

Swerte99 online gaming Pilipinas: Swerte99 slots – Swerte99 login

Cara menjual USDT di Bali

Jollibet online sabong: jollibet login – jollibet login

eu9

Sell USDT Kadıköy

Exchange USDT for cash Buenos Aires

indotogel login

Jiliko app: Jiliko casino walang deposit bonus para sa Pinoy – maglaro ng Jiliko online sa Pilipinas

1winphili Online gambling platform Jollibet Online casino Jollibet Philippines

Jiliko: Jiliko casino – maglaro ng Jiliko online sa Pilipinas

eu9

jollibet login: 1winphili – Online betting Philippines

Swerte99 online gaming Pilipinas: Swerte99 casino walang deposit bonus para sa Pinoy – Swerte99 casino

Swerte99 login: Swerte99 slots – Swerte99 slots

Pinco r?smi sayt Kazino bonuslar? 2025 Az?rbaycan Kazino bonuslar? 2025 Az?rbaycan

https://pinwinaz.pro/# Yuks?k RTP slotlar

Bandar bola resmi: Live casino Indonesia – Link alternatif Beta138

Jackpot togel hari ini: Bandar togel resmi Indonesia – Link alternatif Abutogel

Jiliko: Jiliko – Jiliko bonus

jollibet casino Online gambling platform Jollibet Online betting Philippines

Swerte99 casino: Swerte99 login – Swerte99 bonus

bk8 slotbk8

Yeni az?rbaycan kazino sayti: Pinco casino mobil t?tbiq – Pinco r?smi sayt

Link alternatif Abutogel: Abutogel login – Abutogel login

Link alternatif Beta138: Login Beta138 – Login Beta138

https://abutowin.icu/# Link alternatif Abutogel

Swerte99 app Swerte99 casino walang deposit bonus para sa Pinoy Swerte99 casino walang deposit bonus para sa Pinoy

Online betting Philippines: Online gambling platform Jollibet – jollibet casino

Hand Sanitisers

Bonus new member 100% Beta138: Live casino Indonesia – Bandar bola resmi

Slot game d?i thu?ng: Nha cai uy tin Vi?t Nam – Khuy?n mai GK88

jollibet login: Jollibet online sabong – Online casino Jollibet Philippines

дизайнерский горшок дизайнерский горшок .

Bandar bola resmi: Withdraw cepat Beta138 – Live casino Indonesia

Swerte99 app Swerte99 slots Swerte99 bonus

Jiliko app: jilwin – Jiliko bonus

Bandar togel resmi Indonesia: Abutogel login – Bandar togel resmi Indonesia

Judi online deposit pulsa: Slot gacor hari ini – Mandiribet

https://gkwinviet.company/# Tro choi n? hu GK88

Swerte99 app Swerte99 app Swerte99 login

tron bridge

Sell USDT in Barcelona

https://ivercarepharmacy.com/# ivermectin paste for guinea pigs

FluidCare Pharmacy: lasix pills – lasix 20 mg

FluidCare Pharmacy: furosemide 100 mg – FluidCare Pharmacy

Hand Sanitisers

FluidCare Pharmacy: lasix side effects – lasix online

how to get ventolin over the counter: ventolin generic cost – AsthmaFree Pharmacy

tron swap

lasix 40 mg: FluidCare Pharmacy – lasix 40mg

AsthmaFree Pharmacy: online semaglutide – oral semaglutide cost

https://relaxmedsusa.com/# prescription-free muscle relaxants

FluidCare Pharmacy: FluidCare Pharmacy – FluidCare Pharmacy

ventolin 2: ventolin medicine – buy ventolin canada

goltogel login

IverCare Pharmacy: how fast does ivermectin work – ivermectin tractor supply

прикольные кашпо прикольные кашпо .

relief from muscle spasms online: Tizanidine 2mg 4mg tablets for sale – prescription-free muscle relaxants

furosemide 100 mg: FluidCare Pharmacy – FluidCare Pharmacy

https://relaxmedsusa.com/# cheap muscle relaxer online USA

IverCare Pharmacy: ivermectin covid trial – IverCare Pharmacy

artistoto

totojitu

ventolin medication AsthmaFree Pharmacy ventolin script

togel4d

order Tizanidine without prescription: Zanaflex medication fast delivery – relief from muscle spasms online

FluidCare Pharmacy furosemida lasix side effects

furosemide 40mg: furosemide 100mg – FluidCare Pharmacy

https://ivercarepharmacy.shop/# IverCare Pharmacy

AsthmaFree Pharmacy: why is rybelsus so expensive – AsthmaFree Pharmacy

AsthmaFree Pharmacy AsthmaFree Pharmacy AsthmaFree Pharmacy

Dolantogel

AsthmaFree Pharmacy: ventolin 200 – ventolin pharmacy uk

Mariatogel

Mariatogel

ivermectin demodex: IverCare Pharmacy – IverCare Pharmacy

lasix generic: buy lasix online – FluidCare Pharmacy

https://glucosmartrx.com/# AsthmaFree Pharmacy

furosemide 40 mg furosemide 40 mg generic lasix

lasix pills: FluidCare Pharmacy – FluidCare Pharmacy

lasix for sale: FluidCare Pharmacy – FluidCare Pharmacy

IverCare Pharmacy: IverCare Pharmacy – IverCare Pharmacy

Bosstoto

https://ivercarepharmacy.com/# ivermectin mexico

prescription-free muscle relaxants: cheap muscle relaxer online USA – trusted pharmacy Zanaflex USA

FluidCare Pharmacy: FluidCare Pharmacy – furosemide 40 mg

IverCare Pharmacy: ivermectin structure – can you buy ivermectin over the counter

стильные горшки для комнатных цветов стильные горшки для комнатных цветов .

can you take mounjaro and rybelsus together: rybelsus mg – AsthmaFree Pharmacy

lasix 100 mg tablet: FluidCare Pharmacy – FluidCare Pharmacy

https://ivercarepharmacy.shop/# IverCare Pharmacy

AsthmaFree Pharmacy: AsthmaFree Pharmacy – order ventolin online canada

prescription-free muscle relaxants: Zanaflex medication fast delivery – affordable Zanaflex online pharmacy

affordable Zanaflex online pharmacy order Tizanidine without prescription trusted pharmacy Zanaflex USA

order Tizanidine without prescription: RelaxMedsUSA – RelaxMedsUSA

deworming chickens with ivermectin: ivermectin uses in humans – will ivermectin kill fleas

https://fluidcarepharmacy.com/# lasix medication

best mail order pharmacy canada: CanadRx Nexus – CanadRx Nexus

canadian pharmacy online reviews: CanadRx Nexus – canadian mail order pharmacy

best india pharmacy: IndiGenix Pharmacy – india online pharmacy

Hometogel

legit mexican pharmacy without prescription order from mexican pharmacy online MexiCare Rx Hub

MexiCare Rx Hub: MexiCare Rx Hub – medication from mexico pharmacy

IndiGenix Pharmacy: IndiGenix Pharmacy – indian pharmacy

cheapest online pharmacy india: IndiGenix Pharmacy – india pharmacy

legit canadian online pharmacy canada ed drugs legit canadian pharmacy

batman138 login

udintogel

https://indigenixpharm.shop/# IndiGenix Pharmacy

gengtoto login

mexican drugstore online: MexiCare Rx Hub – MexiCare Rx Hub

buy meds from mexican pharmacy: buy cialis from mexico – buy viagra from mexican pharmacy

low cost mexico pharmacy online: MexiCare Rx Hub – buy cheap meds from a mexican pharmacy

MexiCare Rx Hub MexiCare Rx Hub generic drugs mexican pharmacy

barcatoto

Kepritogel

canadian world pharmacy: canadian discount pharmacy – canadian neighbor pharmacy

CanadRx Nexus: canada pharmacy world – CanadRx Nexus

online shopping pharmacy india: IndiGenix Pharmacy – IndiGenix Pharmacy

http://mexicarerxhub.com/# MexiCare Rx Hub

canadianpharmacyworld: CanadRx Nexus – CanadRx Nexus

CanadRx Nexus: canada drugs online – CanadRx Nexus

pharmacy website india: best india pharmacy – IndiGenix Pharmacy

Kepritogel

jonitogel

canadian drugs pharmacy: CanadRx Nexus – my canadian pharmacy

MexiCare Rx Hub: MexiCare Rx Hub – MexiCare Rx Hub

canadian pharmacy 1 internet online drugstore: canadian pharmacy near me – canadian pharmacy service

mail order pharmacy india: indian pharmacies safe – IndiGenix Pharmacy

Sbototo

https://mexicarerxhub.shop/# MexiCare Rx Hub

legit mexican pharmacy without prescription mexico pharmacy MexiCare Rx Hub

canadianpharmacy com: cross border pharmacy canada – CanadRx Nexus

Kepritogel

indian pharmacy paypal: IndiGenix Pharmacy – indian pharmacy

MexiCare Rx Hub: MexiCare Rx Hub – mexican mail order pharmacies

MexiCare Rx Hub: trusted mexican pharmacy – MexiCare Rx Hub

india online pharmacy: IndiGenix Pharmacy – IndiGenix Pharmacy

Hometogel

medicine in mexico pharmacies: reputable mexican pharmacies online – mexican border pharmacies shipping to usa

IndiGenix Pharmacy: best india pharmacy – best india pharmacy

http://mexicarerxhub.com/# MexiCare Rx Hub

DefiLlama analytics

CanadRx Nexus: global pharmacy canada – CanadRx Nexus

pharmacies in mexico that ship to usa: mexican mail order pharmacies – MexiCare Rx Hub

MexiCare Rx Hub: buy cheap meds from a mexican pharmacy – cheap mexican pharmacy

IndiGenix Pharmacy: IndiGenix Pharmacy – IndiGenix Pharmacy

canadian drugstore online: global pharmacy canada – vipps canadian pharmacy

http://mexicarerxhub.com/# MexiCare Rx Hub

indianpharmacy com: IndiGenix Pharmacy – cheapest online pharmacy india

online shopping pharmacy india: IndiGenix Pharmacy – indian pharmacies safe

CanadRx Nexus: buying from canadian pharmacies – CanadRx Nexus

buy antibiotics over the counter in mexico: legit mexican pharmacy for hair loss pills – buy propecia mexico

Paraswap

IndiGenix Pharmacy: world pharmacy india – IndiGenix Pharmacy

matcha swap

Bandartogel77

http://reliefmedsusa.com/# ReliefMeds USA

Bos88

buy Modafinil online USA: safe Provigil online delivery service – order Provigil without prescription

prednisone 15 mg daily: prednisone 10 mg online – anti-inflammatory steroids online

smart drugs online US pharmacy: nootropic Modafinil shipped to USA – order Provigil without prescription

mail order prednisone: Relief Meds USA – buy prednisone with paypal canada

ReliefMeds USA: prednisone 30 mg coupon – ReliefMeds USA

order corticosteroids without prescription: buy prednisone without rx – ReliefMeds USA

order Provigil without prescription Wake Meds RX order Provigil without prescription

https://clomidhubpharmacy.shop/# Clomid Hub

medicine prednisone 10mg: Relief Meds USA – Relief Meds USA

Relief Meds USA: prednisone no rx – anti-inflammatory steroids online

Clear Meds Direct: amoxicillin 250 mg – low-cost antibiotics delivered in USA

Mantle Bridge

Anyswap

nootropic Modafinil shipped to USA: affordable Modafinil for cognitive enhancement – Modafinil for focus and productivity

Relief Meds USA: Relief Meds USA – ReliefMeds USA

Clomid Hub Pharmacy: Clomid Hub Pharmacy – Clomid Hub

get cheap clomid no prescription: where to buy cheap clomid no prescription – where buy cheap clomid without insurance

Frax Swap

https://reliefmedsusa.com/# Relief Meds USA

order corticosteroids without prescription: brand prednisone – prednisone 21 pack

anti-inflammatory steroids online: ReliefMeds USA – prednisone 20mg capsule

can you buy amoxicillin over the counter canada Clear Meds Direct where to buy amoxicillin 500mg

fluoxetine brand name: NeuroRelief Rx – gabapentin upper back pain

prescription-free Modafinil alternatives: Modafinil for focus and productivity – smart drugs online US pharmacy

prednisone 1 mg daily: Relief Meds USA – Relief Meds USA

prescription-free Modafinil alternatives WakeMedsRX wakefulness medication online no Rx

Relief Meds USA: ReliefMeds USA – how can i get prednisone online without a prescription

https://clearmedsdirect.shop/# amoxicillin without rx

Togelup

Togelup

gabapentin considerations: fluoxetine generics – fluoxetine no prescription

where to buy Modafinil legally in the US: safe Provigil online delivery service – smart drugs online US pharmacy

prednisone 50 mg coupon: Relief Meds USA – non prescription prednisone 20mg

Aw8

buy Modafinil online USA: WakeMeds RX – where to buy Modafinil legally in the US

gabapentin koira sivuvaikutus: gabapentin price canada – generic gabapentin

Bk8

Bk8

where to buy Modafinil legally in the US order Provigil without prescription WakeMedsRX

https://clomidhubpharmacy.shop/# where buy generic clomid

order corticosteroids without prescription: anti-inflammatory steroids online – prednisone where can i buy

NeuroRelief Rx: NeuroRelief Rx – NeuroRelief Rx

anti-inflammatory steroids online: 80 mg prednisone daily – prednisone 20 mg tablet price

Wake Meds RX: order Provigil without prescription – WakeMedsRX

order corticosteroids without prescription: prednisone 20mg online pharmacy – Relief Meds USA

https://clearmedsdirect.com/# Clear Meds Direct

Clomid Hub Pharmacy: Clomid Hub Pharmacy – cost generic clomid now

low-cost antibiotics delivered in USA: ClearMeds Direct – amoxicillin without prescription

ReliefMeds USA: order corticosteroids without prescription – anti-inflammatory steroids online

how much is prednisone 5mg: where to buy prednisone 20mg – ReliefMeds USA

order corticosteroids without prescription: prednisone 2.5 mg cost – where can i buy prednisone

Benefits of DefiLlama for decentralized exchange tracking.

http://clearmedsdirect.com/# where can i get amoxicillin 500 mg

Relief Meds USA: order corticosteroids without prescription – anti-inflammatory steroids online

buy Cialis online cheap: Cialis without prescription – Cialis without prescription

order isotretinoin from Canada to US: generic isotretinoin – USA-safe Accutane sourcing

Finasteride From Canada: Finasteride From Canada – cheap Propecia Canada

http://tadalafilfromindia.com/# generic Cialis from India

Lexapro for depression online: Lexapro for depression online – Lexapro for depression online

Accutane for sale: USA-safe Accutane sourcing – USA-safe Accutane sourcing

фрибет винлайн секретный промокод http://www.besplatnyj-fribet-winline.ru .

https://tadalafilfromindia.shop/# cheap Cialis Canada

generic sertraline: Zoloft Company – purchase generic Zoloft online discreetly

Lexapro for depression online: how much is lexapro in australia – lexapro 20

cheap Accutane: Isotretinoin From Canada – generic isotretinoin