Gilles Olakounlé Yabi

I must admit that I have long been uninterested in debates on racism and the specific condition of “black”, “Afro-descendant” populations in Europe and the United States. I was not insensitive to it, far from it, but I considered that for us black sub-Saharan Africans, wherever we live at any given moment, our priority should be to contribute, to the extent of our capacities, our aptitudes, the opportunities that were offered to us in our life paths, to the improvement of collective well-being in each of our countries, in our part of Africa, in our continent.

I preferred to regard myself and be equally regarded as an individual, a human being, born in an African country of parents who were themselves born in an African country, identified internationally as the Republic of Benin. I expected to be considered Beninese, but also as an African from the part of the continent where one is usually born with a colour that varies between dark pink, light brown, dark brown and black. Colour was far from being a defining trait that could say anything meaningful about my person. During my ten years of higher education in France, colour was of course a little more important in the way others looked at me, and inevitably in the way I looked at myself, than when I was growing up in Cotonou, or since I moved to Senegal, to my part of the world, to Africa, to West Africa, where I feel most at home.

So, yes, despite a few small recollections of mean-spirited behaviour that were as stupid as they were racist, or as racist as they were stupid – and also usually fuelled by ignorance and/or pathological malaise – racism had never intensely mobilized my attention. While I had heard the names of some of the brilliant black writers and essayists who had written some of the most Incredible, accurate, and powerful texts on racism in America and elsewhere in the world, it is with some shame that I must admit that I have only a handful of reference text on the subject. This means that I am still discovering some of James Baldwin’s writing today. Among many others.

Despite a few small recollections of mean-spirited behaviour that were as stupid as they were racist, or as racist as they were stupid – and also usually fuelled by ignorance and/or pathological malaise – racism had never intensely mobilized my attention

I belong to the generation that finds it harder to take the time to read a novel or an essay than to watch a film adapted from a book on the Internet or, better still, on an airplane during a long flight. It is cinema that has made me increasingly sensitive to the long and odious history of racism of which black people were, and still are, the most important victims on a global scale. I remember being on two successive long-distance flights and watching “12 years a Slave“, “Hidden Figures” and…”All Eyez on Me “… Yes, the film about the tragic life and death of rap star Tupac Shakur is also a film about racism and the black condition in the United States. Like far too many African Americans, the likelihood of him ending up dead or in jail before reaching the age of 30 was abnormally high from birth.

The movie “Hidden Figures” released in 2016, tells the compelling story of three African-American “calculators” — mathematicians, physicists and aeronautical engineers Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan and Mary Jackson — who contributed dramatically to the success of NASA’s aviation and space programs in the 1960s. These extremely gifted women had to walk hundreds of yards to get to the only bathrooms permitted for use by black people, as they were barred from using their white colleagues’ comfortable ones. That was only six decades ago. One of these women, Katherine Johnson, passed away earlier this year, on February 24, 2020.

When one learns more about these moments in history, from the nearest to the farthest, from the United States to Brazil, from Haiti to the independent State of the Congo – the former name of Democratic Republic of the Congo -, from Cameroon to apartheid South Africa or Namibia, one can no longer ignore the question of racism which has facilitated, accompanied and been used as a justification for slavery, colonial exploitation and the segregation policies enshrined in laws in countries that claimed to embody the values of civilization. It can no longer be thought – as I once thought – that Africans were doing too much by invoking at every opportunity the menace of racism, slavery, colonization, neo-colonization and subjugation of black populations, in new, more discreet forms whether they live in Africa, the Americas, Europe or elsewhere in the world.

These extremely gifted women had to walk hundreds of yards to get to the only bathrooms permitted for use by black people, as they were barred from using their white colleagues’ comfortable ones. That was only six decades ago

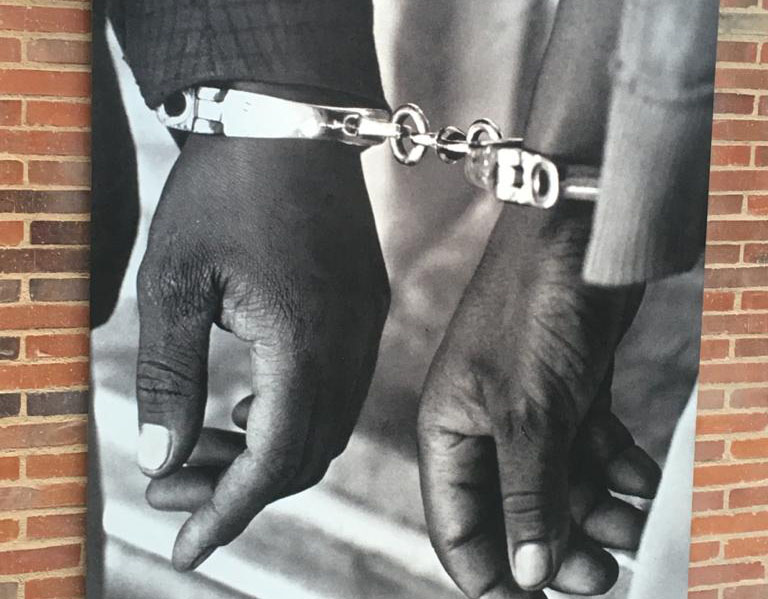

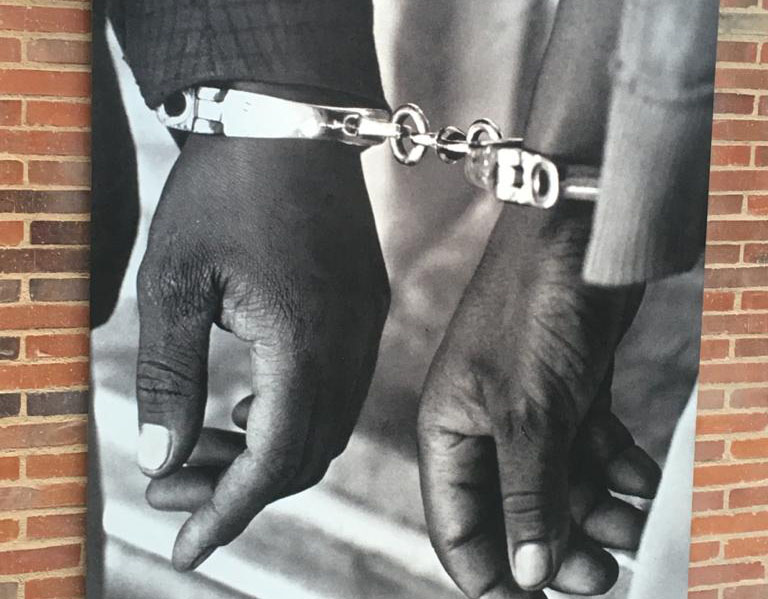

Racism does not explain everything. But racism does exist. It is despicable. It is foul. It rots the lives of far too many Africans and Afro-descendants. None of us, insignificant human beings passing through, know why we were born in this particular century and not in another, or why we were born in this part of the world and not in another. Only a few decades ago, the hooded Ku Klux Klan still lynched blacks in the United States with impunity. Black Americans were still considered second-class human beings. The era of racial segregation, always to the disadvantage of blacks, is extraordinarily recent.

Racism must therefore be combated, and when we are presented with a small historic opportunity to knock it out, or at least to restrict it to a few increasingly isolated pockets of imbeciles – in the true sense of the word – we must not hesitate for a second. The current period looks like such a moment. The year 2020 seems to be propitious to the accelerations of history, from an unexpected global pause that paradoxically created the conditions for several accelerations. No justice no peace, they proclaim in the United States and in demonstrations in many cities around the world. It is comforting to see in the streets here and there crowds with a thousand colours of skin and hair. Blonde, chestnut, brown, black, straight, curly, frizzy hair… No justice, no peace. That’s all.

All too often, individuals and groups who have been robbed, humiliated, crushed, have been told to calm down, to forgive, to pray, to sing gospel songs, to forget and above all never to use violence to express their frustration and their pain in the face of violence inflicted by others. Even when their children were killed because the colour of their skin meant they were perceived as suspicious and dangerous. There has been no call to violence from the strong and inspiring voices that carry the “Black Lives Matter” movement in the United States, such as the charismatic Tamika Mallory. But also, no useless convolutions and unproductive angelism either. No justice no peace. Full stop. It may last for years, maybe even decades, but without a clear sign of the beginning of equal treatment before the law, violence will return, inevitably. No justice no peace. “The fire, next time” Baldwin wrote. This is not a disguised call to violence. It is, unequivocally, a call to reason.

Racism must therefore be combated, and when we are presented with a small historic opportunity to knock it out, or at least to restrict it to a few increasingly isolated pockets of imbeciles – in the true sense of the word – we must not hesitate for a second. The current period looks like such a moment

Meanwhile, where are we on the continent of Africans, the continent where most Africans feel they are at home, where they may suffer for many reasons, but not because of the colour of their skin? In the whole of Africa, this assertion is not entirely true. In North Africa, racism against Blacks is also well established and very old. As elsewhere, it is by no means a defining characteristic of the whole society. Obviously. Neither does it characterize the United States nor Brazil. But let’s face it: in North African countries, the darker the colour of the skin, the more likely you are to be insulted and sometimes brutalized by light-skinned African brothers. It is only in the suburbs of European cities that Blacks and North Africans, living in the same inhospitable low-cost buildings, are close “brothers” united against the racism they are faced with from certain police officers.

“The fire, next time” Baldwin wrote. This is not a disguised call to violence. It is, unequivocally, a call to reason

Therefore, in the countries of North Africa, which are all members countries of the African Union, the issue of racism must be brought to the fore of public debate. A small voice should whisper in the ears of the political authorities and opinion leaders of the North African countries including their religious leaders who are supposed to carry the message of equality of all members of the Muslim community across borders and skin colours. It is not acceptable to remain silent when young black Africans are left to die in the desert, when migrants are martyred, when black African brothers are treated like slaves, or when they are sold at auctions, as was recently the case in Libya. In North Africa too, dark-skinned Africans want to breathe.

And what do we do in the meantime in the part of the world where black Africans do not fear being shot by the police because they are black? It all depends on exactly what part of the continent you find yourself in. Let’s limit ourselves, for illustration purposes, to West and Central Africa. In most countries, generally speaking, the chances of an ordinary resident being killed by a police officer without posing a serious threat to the life of another are low, if not very low. People can be insulted or even physically assaulted when they are in the wrong place at the wrong time, or when they show disrespect or tactlessness towards members of the security forces, and this is usually in countries with the weakest and most dysfunctional states.

It is not acceptable to remain silent when young black Africans are left to die in the desert, when migrants are martyred, when black African brothers are treated like slaves, or when they are sold at auctions, as was recently the case in Libya. In North Africa too, dark-skinned Africans want to breathe

In my African part of the world, as in other parts of the world, the poorer one appears to be, the more likely one is exposed to humiliation and brutality by the security forces. There is nothing particularly African about that. Everywhere, whether one is black, brown, blue or white, it is better to appear rich, well-groomed, or connected to at least a few people who matter, than poor, marked by the difficulties of daily life and lacking social capital, if one wants to greatly reduce the risks of being oppressed, harassed, or humiliated. Generally, however, the risk of being shot dozens of times in the body, or of being suffocated by a knee, is fairly low.

In Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger, Cameroon and Nigeria, hundreds of lives have been lost in recent years due to fatal encounters with security forces, often from the military and paramilitary forces. Usually far from the capitals and big cities. Also usually in a context of terrorism and armed insurgencies, but in many documented incidents, unarmed civilians – sometimes including the elderly and young children who pose no threat – have been murdered. The most recent events in Mali and Burkina Faso again involved victims from the same ethno-cultural group, the Fulani.

In Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger, Cameroon and Nigeria, hundreds of lives have been lost in recent years due to fatal encounters with security forces, often from the military and paramilitary forces

In Burkina Faso, twelve men were most likely executed last May while they were under arrest and therefore posed no threat to the gendarmes on duty. Were some of them really linked in one way or another to a terrorist group? Perhaps. Perhaps not. But we’ll most likely never know. The relatives of the victims – who lived and died anonymously, without anyone being able to post a video of their ordeal on Facebook Live – know a thing or two: they were taken alive, then a few days later they found them dead and had difficulty recognising the bodies that were then presented to them, which were already in a very bad condition.

The parents also know that the victims of this event, which have become recurrent in the troubled part of the territory, are Fulani. Unbearable images circulate in WhatsApp groups, feeding frustration, anger, hatred and desires for revenge or at least self-protection. The messages and images, some of them authentic and some of them fake, mobilize Fulani communities far beyond the borders of the countries concerned. Reactions are still timid, measured and reasonable. But for how long?

The war against terrorism in the Sahel, as everywhere it is proclaimed as a top priority, has for years been the breeding ground for an upsurge in targeted violence against one ethnic community or another in regions where the social ties between different ethno-cultural groups are centuries old. Despite the recurrence of mass killings, despite the denunciations of a few human rights organizations, despite the accumulation of reports documenting crimes committed by elements of the armed forces, emotion remain subdued in West Africa, both at the political level and within civil society. Everyone seems to be really concerned only when a massacre claims victims among their “relatives”, from the same ethno-cultural group.

The war against terrorism in the Sahel, as everywhere it is proclaimed as a top priority, has for years been the breeding ground for an upsurge in targeted violence against one ethnic community or another in regions where the social ties between different ethno-cultural groups are centuries old

This is not racist violence against Blacks inflicted by Whites. But when so little consideration seems to be given to the lives of other human beings on the basis of ethnicity, aren’t we getting very close to the odious mechanics of racism? When there is little or no response to extrajudicial executions of civilians in appalling circumstances, is it not a signal that not all lives are equally valuable? So, yes, the victims in the Sahel region are regarded first of all as villagers, poor people from isolated regions – because nothing has been done to connect them to the modernity of the capitals – before they are presumed Fulani who are close to or lenient with the armed Islamist terrorist groups.

One’s position in socio-economic stratification is always a significant factor in determining the level of one’s vulnerability. But the ethnic prism used in the perception of those who would be regarded as more dangerous and less reliable than others is today unquestionable in many countries of the Sahel and beyond. It fuels a deep malaise and endangers the entire West African region. We are playing with fire. We have already forgotten that some Africans in the Great Lakes region – long after the departure of others who for a long time described us as savages while sowing inhuman violence here and there – were able to commit genocide, the worst of all mass crimes.

We must make this year 2020, so unpredictable, so crazy, the year of the dismantling of the global factory of production and reproduction of inequality, injustice, impunity and contempt for the weakest and the most vulnerable among us

We had better not see the fire breaking out only in the United States. “No justice, no peace”, the African Americans are chanting there. “No justice, no peace”, we should cry out in chorus on African soil while thinking of the black victims of the United States of which George Floyd is the latest symbol, but not only. We must make this year 2020, so unpredictable, so crazy, the year of the dismantling of the global factory of production and reproduction of inequality, injustice, impunity and contempt for the weakest and the most vulnerable among us. The cynical factory that gnaws at our humanity is global but its subsidiaries are everywhere. From northern Burkina Faso to central Mali, from western Cameroon to northern Nigeria, from the city of Minneapolis to Rio de Janeiro, from eastern Democratic Republic of Congo to what remains of Yemen or Syria. No justice, no peace.

Crédit photo : © Gilles Yabi

Economist and political analyst, Gilles Olakounlé Yabi is the President of the Steering Committee of WATHI, the West African Citizens’ think tank. He has been a journalist and director for West Africa of the non-governmental organization International Crisis Group. The opinions expressed are personal. Special thanks to Teniola Tayo for her contribution to the editing of the English version.