Author: Robert Kappel

Affiliated organization: Library FES

Type of publication: Report

Date of publication: January 2021

EU-African economic relations

European and African countries are at different stages of economic development, with European gross domestic product (GDP) more than ten times that of sub-Saharan Africa. Africa’s GDP, while recording average annual growth of 4.6 per cent over the last 20 years, has not grown evenly across the continent. Nigeria and South Africa have been languishing for a long time and, as a result, are depressing the continent’s average economic growth. Other countries, such as Ethiopia or Rwanda, on the other hand, recorded very high growth.

Although average per capita income has been on the increase for the last 15 years, the current trends suggest that by 2030, around 380 million Africans will still be living in poverty. Most African countries do not converge. One of the reasons for this is the lack of economic dynamism. Africa is falling behind other continents, rather than catching up, despite its relatively high growth. That said, following the lost decades of the 1980s and ‘90s, many African countries are now undergoing fundamental transformation. Thanks to urbanisation, digitalisation, integration into regional and global value chains, modernisation of agriculture and a new generation of dynamic young Africans, African populations are becoming increasingly self-confident. Another harsh reality, however, is that in some African countries, clientelist rulers have not embarked on the path of modernity and reform, but remain focused on keeping hold of power instead.

Trade

Africa currently accounts for less than three per cent of global trade. In 1980, the corresponding figure still remained at 4.6 per cent but dropped to below two per cent in the 1990s, before increasing slightly post-2000. This latter development can partly be put down to rising export prices as well as increasing foreign direct investment (FDI), both of which contributed to increased trade. Above all, however, it can be attributed to the high demand for raw materials in China.

The EU is Africa’s largest trade partner, although Africa’s share of exports to the EU has been on the decline for a number of years now. This shift is mainly due to the fact that European countries have diversified their imports of raw materials, and other countries – such as China, India, Turkey and the Gulf countries – have linked their rise to the expansion of their commodity trade with Africa. In 2018, trade in goods between the 27 EU Member States and Africa reached a total value of 235 billion euros (32 per cent of Africa’s total trade). Africa’s trade with China by comparison amounted to 125 billion euros (17 per cent), while trade with the USA totalled 46 billion euros (six per cent).

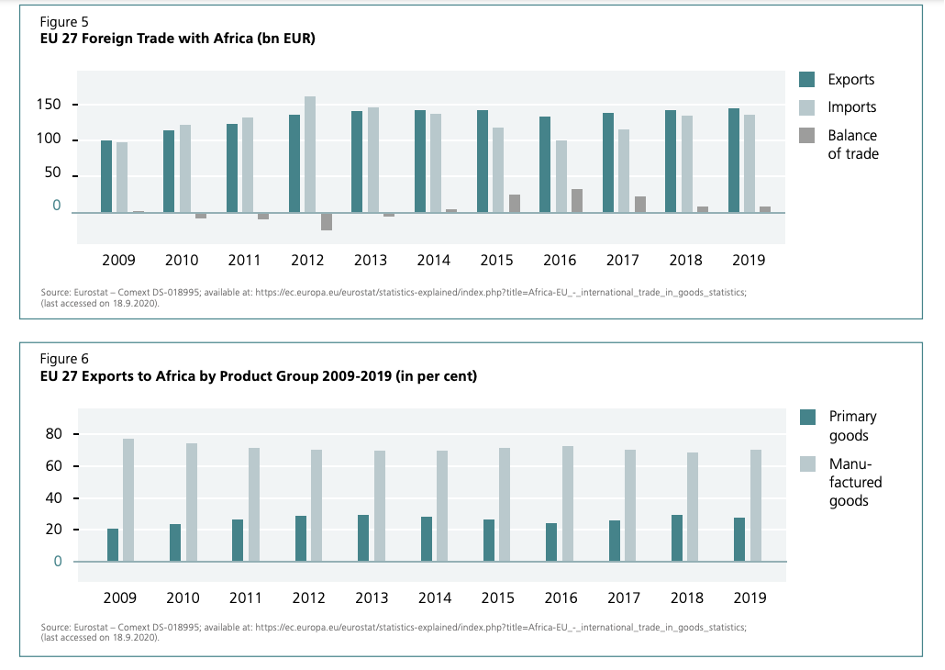

In 2009, the EU’s exports from and imports to Africa were more or less balanced. The European trade surplus was as little as 2.3 billion euros (see Figure 5). In the subsequent years, both imports from and exports to Africa increased, although there was slightly more growth in imports. This trend continued into 2012 when the European trade deficit reached 25 billion euros, which was largely a result of the increase in the price of raw materials. After 2012, imports from Africa declined, while European exports continued to grow. 2014 was a turning point, with the trade deficit turning into a 5.1 billion euro surplus. In 2016, the EU surplus in commodity trading surged to a record 33 billion euros. Growing imports from Africa subsequently resulted in a decline in the European trade surplus.

Industrial goods made up the lion’s share of European exports to Africa, with 77 per cent of EU exports to Africa in 2009 being manufactured goods. This dropped to 68 per cent in 2019, while the share of primary goods rose from 20 to 32 per cent. The declining share of manufactured goods was caused primarily by the decrease in machinery and vehicle exports as a share of total European exports to Africa (42 per cent in 2009, 36 per cent in 2019). A considerable proportion of raw materials exports are food products, accounting for approximately 14 per cent of total European raw materials exports since the 1980s.

Primary goods dominate Africa’s exports to Europe. Between 2009 and 2019, however, their share dropped from 77 to 66 per cent, primarily due to the declining share of energy exports resulting from falling oil and gas prices. During the same period, the share of industrial goods increased from 21 to 32 per cent. This is largely due to the increase in exports of machinery and vehicles from South Africa and North African countries.

The composition of exports and imports is also different, with Africa exporting mainly unprocessed raw materials and agricultural products and the EU’s exports to Africa mainly comprising capital and consumer goods. Exceptions here are the North African countries of Morocco, Tunisia and Egypt, as well as Mauritius, Kenya and South Africa, which have a more diversified export structure. Some countries such as Ethiopia and Senegal, for instance, have also successfully industrialised in the last few years and are now exporting more manufactured goods.

North Africa8 is the EU’s largest African trade partner. Goods exports from the EU to North Africa increased from 54 billion euros in 2009 to 76 billion euros in 2019, which corresponds to an average annual growth rate of 3.5 per cent. Growth rates for trade with East Africa was even higher (5.7 per cent), closely followed by West Africa (5.4 per cent) and Southern Africa (5.2 per cent). Goods exports to Central Africa, in contrast, declined during this period (2.3 per cent).

Investment

The African continent remains a peripheral region when it comes to international investment activity. While Africa’s share in international investment was still around the 5.3 per cent mark in 1967, by 1980 it had plummeted to 2.6 per cent, subsequently falling to some two per cent by 2018. The importance of foreign direct investment inflows and stocks to and in Africa is declining. Investment data since the 1980s show that Africa’s declining share of global investment appears to be of a longer-term nature.

Primary goods dominate Africa’s exports to Europe. Between 2009 and 2019, however, their share dropped from 77 to 66 per cent, primarily due to the declining share of energy exports resulting from falling oil and gas prices. During the same period, the share of industrial goods increased from 21 to 32 per cent. This is largely due to the increase in exports of machinery and vehicles from South Africa and North African countries

In 2017, direct investment from Europe amounted to 222 billion euros (capital stock), which was five times higher than investment from the USA (42 billion euros) and China (38 billion euros). British, French, Dutch and Italian companies are the most important European investors in the African continent. Over the last ten years, Chinese FDI has been on a sharp upward trajectory placing it in fourth position when it comes to inflows after the USA, UK and France. China’s FDI stock in Africa is still lower than that of European countries, amounting to just 15 per cent of total European FDI inflows. Our statistical analysis also illustrates that, although the PRC has become an important investor, the gap between the EU and China is getting bigger rather than smaller. This is largely being caused by the steeply increasing Italian and Dutch investment volumes, which have compensated for the decline in FDI from France and the UK.

Germany, too, is an important investor in the African continent (ranking tenth for FDI stocks in Africa). Its investment structure differs significantly from the other countries, however. The UK, France and the USA invest mainly in the raw materials and financial services sectors, while Germany is very strongly represented in industrial sectors. Germany’s main investment focus is car and auto parts manufacturing. This diagram presents a highly distorted picture, however. A significant share of German FDI is directed to the automotive and automotive parts manufacturing sector in South Africa. Removing South Africa from the equation would deliver a far less favourable picture of the sectoral distribution.

Compared with companies from the USA, France, the UK, China, South Africa and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), German investors create more jobs per one million US dollars invested (see Table 1, Figure 19). The reason for this is that German businesses invest predominantly in the manufacturing industry. The large number of jobs created can essentially be explained by Germany’s high level of industrial investment in South Africa and several countries in Northern Africa. These are all middle-income countries with an emerging middle class, a relatively diversified industrial structure and a comparatively strong manufacturing industry.

Between 2000 and 2017, China issued 130 billion euros in loans to African governments and state-owned enterprises, with the funds being used mainly for infrastructure expansion. According to the China Africa Research Institution (CARI), China is now the largest bilateral creditor in the region, accounting for 20 per cent of Africa’s public debt.

In 2017, direct investment from Europe amounted to 222 billion euros (capital stock), which was five times higher than investment from the USA (42 billion euros) and China (38 billion euros). British, French, Dutch and Italian companies are the most important European investors in the African continent

In every respect, the EU is an important external actor for Africa and has indeed been strengthening its position on the African continent rather than scaling down its activities. The increasing share of European FDI in manufacturing and services, in particular, – along with the diminishing focus on the raw materials sector – has enabled European companies to consolidate their economic position. Nevertheless, here too, caution is called for: Contrary to all assertions, FDI and trade – and this includes with the EU – are not overly effective. They neither generate a large number of jobs, though certain high-quality investments can give knowledge and technology transfer a boost, nor do they make a significant contribution to industrial or agricultural development on the African continent. As demonstrated below, this is related to the asymmetrical relationship between the two continents, FDI’s weak links with local industry and especially with the endogenous dynamics of Africa’s economic development, which is less dependent on external transfers today than ever before.

Cooperation with Africa: from Lomé to a comprehensive strategy with Africa

In recent years, the European Union and EU member states have developed numerous new Africa strategies. These reflect the challenges of cooperation in very different ways as well as the respective shifts in economic policy. For example, commodity stabilisation policies were linked to the ideas of the New World Economic Order promoted by UNCTAD during the 1970s and stabilisation concepts to the neo-liberal ideas of the Chicago School of the 1980s and the policies of the Thatcher and Reagan administrations, while today’s concepts are partly guided by the ideas of inclusive growth (pro-poor growth), redistribution of global inequality and sustainability agendas.

In as early as 1958, the Treaty of Rome set out the foundations for postcolonial relations between the then European Economic Community and Africa. The subsequent Yaoundé, Lomé and finally Cotonou Agreement between the EU and the African, Caribbean and Pacific Group of States (ACP) created close ties, for example through commodity price stabilisation, development aid, the creation of jointly staffed institutions, and the establishment of an ACP Brussels Office. Measures to promote industrialisation in Africa, however, were not on the agenda.

The Cotonou Agreement signed in 2000 and in particular the Joint Africa-EU Strategy (JAES) adopted in 2007 signalled a gradual turn in the relations between the EU and Africa. Up until then, the relationship had been characterised by postcolonial dynamics. There are four main reasons behind this development: Firstly, China’s strategic approach made it the EU’s main competitor in trade, investment and development cooperation. Secondly, for some 15 years already, African countries had been recording relatively high growth rates. Thirdly, migration from African countries to the EU had been on the rise as a result of conflict and crisis. And, fourthly, numerous new African initiatives, such as the African Union’s Agenda 2063 plan for the transformation of Africa and the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) adopted in 2019, bear witness to the fact that African states are acting increasingly strategically and are exploring opportunities for cooperation with multiple actors.

The JAES adopted in 2007 had already emphasised the need for »a move away from a traditional relationship« to »forge a real partnership characterized by equality«. The Juncker Plan – the Africa-Europe Alliance for Sustainable Investment and Jobs (AEA) aimed to take the development of cooperation with Africa in a new direction. China’s geostrategic moves acted as a catalyst for Europe to develop its own geostrategic concept. The AEA was ultimately replaced by the »Towards a Comprehensive Strategy with Africa« (CSA) proposal in March 2020. The CSA is a European document which serves as a framework for talks between the EU and the AU. The third main agenda dedicated to a new form of cooperation with Africa is the External Investment Plan (EIP).

The challenges facing EU-African relations are immense. Over the next ten years, the focus will be on transforming what has so far been paternalistic cooperation into a strategic partnership. In order to achieve this, however, a number of fundamental decisions need to be made. EU political leaders claim that 2020 is »pivotal year« for the EU’s relationship with Africa. The new EU-Africa Strategy adopted in March 2020 envisages building a »stronger, more ambitious« partnership with Africa. Ahead of the strategy being adopted, the European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen called for a »partnership of equals«, moving beyond the donorrecipient dynamics that have characterised relations between the EU and Africa for so long. Instead, the EU-Africa Strategy seeks to pave the way for genuine cooperation.

Forging a strategic partnership: recommendations for action

Combatting the pandemic

In March 2020, the High Representative of the EU for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Josep Borrell, announced that the EU would be supporting its partners around the world in fighting the virus, particularly those in Africa. This assurance was translated into real action when the EU initiated its »Team Europe« package to support partner countries in the fight against the coronavirus pandemic. The EU and its Member States have taken a variety of initiatives to help Africa tackle the outbreak of Covid-19. These include immediate short-term measures such as the procurement of tests and laboratory equipment, followed by longer term pandemic prevention through the development of the laboratory infrastructure, the provision of funding for training measures, information campaigns and national pandemic response plans.

The EU’s support is crucial and could also help to strengthen Africa’s public health sector in the long term. A whole raft of African initiatives, however, likewise demonstrate how much African countries are taking the reins themselves when it comes to combatting the crisis.

New agricultural policy

A common agricultural policy that serves the interests of both sides and involves the key African and European players must be developed in cooperation with the African countries. One area of focus should comprise measures to ensure or improve food security.

Thanks to its extremely high productivity and billions in subsidies, the European agricultural sector is superior to African agriculture in every respect. It is repeatedly argued that European subsidies exacerbate poverty and food insecurity by facilitating cheap exports. The EU’s Common Agricultural Policy operates via what is known as the »export and import hinge«: »If the EU, the world’s biggest exporter of agricultural products, were to increase its exports, world market prices would fall. They may well also fall in developing countries, undermining their competitiveness and displacing local products«64. European agriculture receives 45 billion euros a year from the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF). These funds primarily benefit farmers and food companies. In 2016, the average subsidies received by farmers amounted for almost 300 euros per hectare, meaning that a farmer with 30 hectares of land would be awarded a direct payment of around 10,000 euros each year. An additional billion euros comes from the European agricultural fund for rural development (EAFRD). This money is earmarked predominantly for environmental protection, climate change mitigation and animal welfare as well as rural development. These substantial direct payments have played an important part in the EU becoming the world’s largest exporter of foodstuffs. African farmers are at a significant competitive disadvantage in every respect due to the protectionist measures of the EU (and also of the USA and China).

Supporting transformation processes

What is also needed is a proactive policy for economic and social transformation. The creation of more productive jobs for Africa’s rapidly growing population is of pivotal importance. Investment in urban agglomerations can be an important driver of structural change. In the cities, in particular, work in the informal sector constitutes the all-important basis of survival for the majority of the population. The pandemic has meant that millions of people working in the informal economy face having their livelihoods destroyed, which is something that has hit the poorest members of the population hardest. For many years, the growth process on the African continent has led to the emergence of a growing middle class, although this class is itself volatile and could slip back into poverty.

Linking foreign direct investment with local businesses

Foreign direct investment (FDI) can make an important contribution to Africa’s economic development, provided it does not merely comprise exploiting raw materials. Investment in agriculture and the manufacturing industry, in particular, but also in the service sector can help create highly skilled jobs and foster technology and knowledge transfer, thus boosting Africa’s productivity development. In many of Africa’s less productive microenterprises, this form of investment is virtually impossible. Instead, for these enterprises to grow, government support initiatives are needed, for instance in the form of vocational training, better access to loans and a reliable supply of electricity.

In many of the countries on the African continent, however, this support has been non-existent. Large-scale and medium-sized enterprises may be developing, but growth is sluggish, meaning they are not really in a position to drive Africa’s economic transformation forward on their own. FDI can help achieve specialisation and generate economies of scale. A number of foreign enterprises are already working in close collaboration with local businesses, creating industrial zones, engaging in long-term projects and contributing capital, knowledge and technology. Fundamental change, however, must take place in Africa itself. In fact, the contribution that foreign direct investment has made to reducing poverty or youth unemployment has proven to be limited.

Total foreign investment in the period 2014 to 2018, for example, led to the creation of as few as 140,000 new jobs per year on average, primarily in Egypt, Ethiopia, Morocco, South Africa, Nigeria, Algeria and Tunisia (in this order). Virtually the only way to create jobs for 20 million people per annum is through local businesses and farmers. And it is down to local governments to support and foster rather than hamper their local economy.

Redefining trade relations

Up till now, trade agreements between the EU und African countries have not been properly regulated. In fact, the EU’s trade and cooperation policy has most certainly been partly responsible for the asymmetrical relations and exacerbated the debt crisis, which is now ramping up again. Africa has largely failed to industrialise, with no Africa-wide industry agenda in place to this day. African and European countries debated the Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) over many years yet failed to come to an agreement. To date, the EU has entered into trade agreements with North African countries and five Economic Partnership Agreements with regional groups of sub-Saharan countries. Critics argue that these agreements might impede the structural transformation of the African continent by undermining intra-regional trade and integration.

Lowering tariffs on EU imports to African markets, as set down in the EPAs, is predicted to divert the region’s trade away from local suppliers towards European manufacturers. With the EU’s EPAs being negotiated with regional blocs as opposed to the African continent as a whole, they have increased the heterogeneity of the liberalisation commitments of African countries, adding to the challenge of rationalising the African continent’s trade regimes under AfCFTA. The limited benefits the EPAs are expected to bring explain why many African countries, especially low-income countries, have refused to join them. The long-overdue reform of the trade regime between the European Union and Africa requires the EPAs to be abandoned. Given the EU Commission’s for global markets to be opened up even further, African businesses and smallholders are at an even greater risk of being marginalised by European imports. To be able to grow and develop competitive industries and agricultural economies, African countries are demanding external protection that will help them compensate for unfavourable locational conditions.

Supporting digital transformation

Another important goal for African countries is the implementation of digital transformation in Africa. In the CSA, the EU makes a strong plea for the development of a digital single market in Africa in order to boost growth across all sectors of the economy. One of the most important prerequisites for participation in the digital transformation, however, is a reliable energy supply, something which is not guaranteed for 60 per cent of the African population.

Supporting debt reduction

Many African countries are at high risk of debt distress. Even before the Covid-19 pandemic, Africa’s growing national debt was the subject of much debate. Numerous experts have proposed a debt moratorium to give Africa leeway to overcome the pandemic crisis. Whether this moratorium would ultimately become a waiver of debt, however, remains unclear. With the IMF classifying 16 of the 36 lowest income countries in sub-Saharan Africa as being »in debt distress« or having a »high risk of debt distress« even before the Covid-19 outbreak, it is very likely that some countries will have difficulties servicing their debts in the near future.

The decision by the G20, the IMF and the Paris Club to offer a temporary suspension of debt as part of the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) caused quite the stir; at just 0.6 per cent of GDP, the impact for Africa, however, was modest to say the least. This is due to the fact that in the past 20 years African countries have increasingly taken on loans at commercial conditions from multilateral creditors (e.g. the World Bank, the African Development Bank), from China as well as on capital markets and with private creditors. In fact, African Eurobond debt increased ten-fold over a period of ten years to 58 billion US dollars (see Figure 21). Neither the Eurobonds nor the commercial loans are covered by the DSSI. The World Bank is not involved in the DSSI either, claiming that, in light of their net resource transfer to African countries, it would make no sense to suspend their debt repayments, and that a moratorium might adversely impact broader poverty reduction efforts. Chinese President Xi Jinping, on the other hand, confirmed that China would be participating in the DSSI, stating that the Chinese government was willing to cancel the sub-Saharan countries’ interest-free debt that was due for payment in 2020.

Les Wathinotes sont soit des résumés de publications sélectionnées par WATHI, conformes aux résumés originaux, soit des versions modifiées des résumés originaux, soit des extraits choisis par WATHI compte tenu de leur pertinence par rapport au thème du Débat. Lorsque les publications et leurs résumés ne sont disponibles qu’en français ou en anglais, WATHI se charge de la traduction des extraits choisis dans l’autre langue. Toutes les Wathinotes renvoient aux publications originales et intégrales qui ne sont pas hébergées par le site de WATHI, et sont destinées à promouvoir la lecture de ces documents, fruit du travail de recherche d’universitaires et d’experts.

The Wathinotes are either original abstracts of publications selected by WATHI, modified original summaries or publication quotes selected for their relevance for the theme of the Debate. When publications and abstracts are only available either in French or in English, the translation is done by WATHI. All the Wathinotes link to the original and integral publications that are not hosted on the WATHI website. WATHI participates to the promotion of these documents that have been written by university professors and experts.

1538 Commentaires. En écrire un nouveau

I personally find that this platform exceeded my expectations with fast transactions and clear transparency.

The best choice I made for cross-chain transfers. Smooth and seamless withdrawals. I moved funds across chains without a problem.

I’ve been active for a week, mostly for using the API, and it’s always quick deposits.

The exploring governance tools are useful analytics and great support.

The using the API tools are responsive team and robust security.

I personally find that the best choice I made for fiat on-ramp. Smooth and great support. My withdrawals were always smooth.

I was skeptical, but after several months of exploring governance, the reliable uptime convinced me.

I value the seamless withdrawals and scalable features. This site is reliable.

I’ve been active for since launch, mostly for providing liquidity, and it’s always responsive team.

The site is easy to use and the clear transparency keeps me coming back. Charts are accurate and load instantly.

The using the mobile app tools are clear transparency and scalable features. My withdrawals were always smooth.

I’ve been using it for a year for using the API, and the stable performance stands out. The dashboard gives a complete view of my holdings.

The using the API process is simple and the seamless withdrawals makes it even better.

I switched from another service because of the scalable features and responsive team.

I switched from another service because of the wide token selection and fast transactions.

Chris here — I’ve tried trading and the clear transparency impressed me. Charts are accurate and load instantly.

I personally find that i’ve been active for half a year, mostly for checking analytics, and it’s always intuitive UI.

I was skeptical, but after half a year of swapping tokens, the reliable uptime convinced me.

The testing new tokens tools are quick deposits and scalable features.

I personally find that i was skeptical, but after a week of portfolio tracking, the stable performance convinced me.

I value the easy onboarding and robust security. This site is reliable. The updates are frequent and clear.

The site is easy to use and the accurate charts keeps me coming back. Definitely recommend to anyone in crypto.

The cross-chain transfers tools are great support and reliable uptime. I moved funds across chains without a problem.

I’ve been using it for recently for fiat on-ramp, and the stable performance stands out.

I personally find that wow! This is a cool platform. They really do have the quick deposits. Support solved my issue in minutes.

dominobet

indratogel

schnelle lieferung tadalafil tabletten: tadalafil 20mg preisvergleich – internet apotheke

http://mannerkraft.com/# gГјnstige online apotheke

Pokerace99

gГјnstigste online apotheke Blau Kraft De online apotheke rezept

tadalafil 20mg preisvergleich: tadalafil erfahrungen deutschland – online apotheke preisvergleich

https://blaukraftde.shop/# apotheke online

sportwetten gratis ohne einzahlung

Check out my site – wettanbieter Vergleich paypal

service roti Sector 2

wettprognosen heute

Review my web-site: Sportwetten bonus Neu

online apotheke rezept: sildenafil tabletten online bestellen – günstige online apotheke

rulment roata Opel

medikament ohne rezept notfall: apotheke ohne wartezeit und arztbesuch – online apotheke deutschland

servetele faciale

consiliere psihologica Constanta

https://mannerkraft.com/# apotheke online

dezvoltare personala copii Constanta

medikamente rezeptfrei: online apotheke – online apotheke versandkostenfrei

internet apotheke diskrete lieferung von potenzmitteln п»їshop apotheke gutschein

https://mannerkraft.com/# eu apotheke ohne rezept

online apotheke preisvergleich: gunstige medikamente direkt bestellen – п»їshop apotheke gutschein

günstige online apotheke: diskrete lieferung von potenzmitteln – online apotheke

online apotheke versandkostenfrei online apotheke deutschland gГјnstige online apotheke

medikamente rezeptfrei: MannerKraft – internet apotheke

dominobet

preisvergleich kamagra tabletten: generisches sildenafil alternative – Viagra online bestellen Schweiz Erfahrungen

online apotheke rezept Blau Kraft De online apotheke rezept

https://mannerkraft.shop/# online apotheke

internet apotheke: viagra ohne rezept deutschland – online apotheke rezept

UFABET

Bk8

internet apotheke diskrete lieferung von potenzmitteln europa apotheke

ufasnakes

online apotheke gГјnstig: Blau Kraft De – online apotheke preisvergleich

Udintogel

günstige online apotheke: Männer Kraft – medikament ohne rezept notfall

ohne rezept apotheke tadalafil 20mg preisvergleich wirkung und dauer von tadalafil

http://blaukraftde.com/# gГјnstigste online apotheke

internet apotheke: sicherheit und wirkung von potenzmitteln – online apotheke versandkostenfrei

cialis generika ohne rezept: cialis generika ohne rezept – günstigste online apotheke

internet apotheke cialis generika ohne rezept tadalafil 20mg preisvergleich

https://gesunddirekt24.shop/# п»їshop apotheke gutschein

internet apotheke: apotheke ohne wartezeit und arztbesuch – online apotheke deutschland

mexican pharmacy online: pharma mexicana – SaludFrontera

http://curabharatusa.com/# CuraBharat USA

safe online pharmacies in canada: TrueNorth Pharm – TrueNorth Pharm

TrueNorth Pharm TrueNorth Pharm canadadrugpharmacy com

https://curabharatusa.shop/# buy antibiotics from india

can i order online from a mexican pharmacy pharmacy mexico SaludFrontera

sportwetten seite

Here is my page – wir wetten bonus, Nathan,

CuraBharat USA: CuraBharat USA – online medicine purchase

https://saludfrontera.shop/# SaludFrontera

https://truenorthpharm.shop/# TrueNorth Pharm

SaludFrontera my mexican pharmacy SaludFrontera

justlend

CuraBharat USA: india online pharmacy – CuraBharat USA

purple pharmacy online ordering: SaludFrontera – reputable mexican pharmacy

https://curabharatusa.com/# indian chemist

oppatoto

SaludFrontera farmacias mexicanas mexican rx

CuraBharat USA: CuraBharat USA – CuraBharat USA

canadian pharmacy 24: TrueNorth Pharm – canada drug pharmacy

mexico pharmacy: SaludFrontera – mexico farmacia

https://truenorthpharm.shop/# TrueNorth Pharm

mexico city pharmacy SaludFrontera SaludFrontera

TrueNorth Pharm: TrueNorth Pharm – TrueNorth Pharm

https://truenorthpharm.com/# canadian pharmacy tampa

CuraBharat USA: CuraBharat USA – CuraBharat USA

Porn

TrueNorth Pharm TrueNorth Pharm cross border pharmacy canada

buchmacher bedeutung

Here is my web site: lizenz sportwetten

buy online medicine: CuraBharat USA – CuraBharat USA

https://saludfrontera.shop/# SaludFrontera

BluePill UK generic sildenafil UK pharmacy BluePill UK

MediTrustUK: discreet ivermectin shipping UK – ivermectin without prescription UK

http://mediquickuk.com/# MediQuickUK

generic and branded medications UK MediQuickUK MediQuickUK

tadalafil generic alternative UK: buy ED pills online discreetly UK – IntimaCare

BluePill UK: BluePill UK – viagra discreet delivery UK

MediQuickUK generic and branded medications UK trusted UK digital pharmacy

http://mediquickuk.com/# generic and branded medications UK

tadalafil generic alternative UK: confidential delivery cialis UK – weekend pill UK online pharmacy

BluePill UK https://bluepilluk.shop/# viagra discreet delivery UK

generic stromectol UK delivery ivermectin cheap price online UK MediTrustUK

trusted UK digital pharmacy: MediQuickUK – generic and branded medications UK

beste sportwetten app android

Look into my web blog … buchmacher bonus ohne einzahlung (Debra)

BluePillUK https://intimacareuk.shop/# confidential delivery cialis UK

justlend

MediTrust UK ivermectin tablets UK online pharmacy MediTrust UK

IntimaCare UK: branded and generic tadalafil UK pharmacy – buy ED pills online discreetly UK

Anyswap

https://bluepilluk.com/# viagra online UK no prescription

IntimaCare UK IntimaCare IntimaCare UK

discreet ivermectin shipping UK: ivermectin tablets UK online pharmacy – trusted online pharmacy ivermectin UK

BluePill UK http://intimacareuk.com/# tadalafil generic alternative UK

MediQuick generic and branded medications UK confidential delivery pharmacy UK

branded and generic tadalafil UK pharmacy: IntimaCare – tadalafil generic alternative UK

sportwetten deutsch

My blog post darts wetten tipico (https://dartswettquoten.Com)

http://bluepilluk.com/# BluePillUK

viagra online UK no prescription http://mediquickuk.com/# MediQuickUK

ivermectin tablets UK online pharmacy stromectol pills home delivery UK stromectol pills home delivery UK

generic stromectol UK delivery: trusted online pharmacy ivermectin UK – generic stromectol UK delivery

does tadalafil lower blood pressure which is better cialis or levitra compounded tadalafil troche life span

https://evergreenrxusas.shop/# EverGreenRx USA

buy cheap tadalafil online: EverGreenRx USA – cialis where can i buy

EverGreenRx USA: buy cialis from canada – EverGreenRx USA

https://evergreenrxusas.com/# EverGreenRx USA

buchmacher england

Feel free to surf to my webpage; ncaa Basketball wett

Vorhersage über tore untertore – https://basketball-wetten.com,

EverGreenRx USA: EverGreenRx USA – EverGreenRx USA

design modern pentru afaceri

EverGreenRx USA: EverGreenRx USA – EverGreenRx USA

EverGreenRx USA EverGreenRx USA sanofi cialis

https://evergreenrxusas.shop/# EverGreenRx USA

EverGreenRx USA: EverGreenRx USA – cialis overnight shipping

EverGreenRx USA: tadalafil softsules tuf 20 – cialis time

slot online: bataraslot 88 – bataraslot login

https://mez.ink/batarabet# bataraslot

betawi77 net betawi77 net betawi 77 slot

Situs Togel Toto 4D: Daftar InaTogel Login Link Alternatif Terbaru – Official Link Situs Toto Togel

bataraslot login bataraslot alternatif bataraslot 88

kratonbet: kratonbet alternatif – kratonbet alternatif

INA TOGEL Daftar: Login Alternatif Togel – Situs Togel Toto 4D

https://linklist.bio/inatogelbrand# Situs Togel Toto 4D

kratonbet link kratonbet alternatif kratonbet login

hargatoto alternatif: hargatoto alternatif – hargatoto login

bataraslot alternatif situs slot batara88 bataraslot login

Situs Togel Terpercaya Dan Bandar: inatogel – INA TOGEL Daftar

betawi77 login betawi 77 slot betawi77 login

https://mez.ink/batarabet# batarabet

inatogel: Official Link Situs Toto Togel – INA TOGEL Daftar

justlend

kratonbet login kratonbet login kratonbet login

https://mez.ink/batarabet# batarabet alternatif

betawi 777: betawi77 net – betawi 777

mawartoto link mawartoto slot mawartoto link

kratonbet: kratonbet login – kratonbet link

Daftar InaTogel Login Link Alternatif Terbaru inatogel Situs Togel Terpercaya Dan Bandar

situs slot batara88: batara vip – batarabet

https://bluepharmafrance.com/# viagra homme

acheter kamagra pas cher livraison rapide Pharma Libre kamagra gel oral livraison discrete France

http://intimapharmafrance.com/# IntimaPharma

PharmaLibre France: commander kamagra en toute confidentialite – kamagra 100 mg prix competitif en ligne

tadalafil prix IntimaPharma commander cialis discretement

IntimaPharma: commander cialis discretement – cialis generique pas cher

IntimaPharma medicament contre la dysfonction erectile cialis original et generique livraison rapide

http://pharmaexpressfrance.com/# pharmacie en ligne france livraison belgique

tadalafil prix: tadalafil sans ordonnance – IntimaPharma France

viagra generique efficace pilule bleue en ligne viagra 100 mg prix abordable France

kamagra oral jelly: acheter kamagra pas cher livraison rapide – kamagra

BluePharma France: livraison rapide et confidentielle – BluePharma France

https://pharmalibrefrance.com/# kamagra oral jelly

medicament contre la dysfonction erectile tadalafil prix IntimaPharma France

commander medicaments livraison rapide: medicaments generiques et originaux France – pharmacie en ligne france fiable

BluePharma: viagra générique efficace – viagra femme

viagra 100 mg prix abordable France BluePharma France viagra generique efficace

tadalafil sans ordonnance: Intima Pharma – Intima Pharma

https://truemedspharm.com/# discount pharmacy mexico

: buy antibiotics online –

TrueMeds TrueMeds Pharmacy TrueMeds Pharmacy

TrueMeds: TrueMeds Pharmacy – TrueMeds

VitalCore: VitalCore – VitalCore

legit online pharmacy trusted online pharmacy TrueMeds

online pharmacy price checker: pharmacy discount coupons – pharmacy near me

https://clearmedspharm.shop/# antibiotics over the counter

VigorMuse Coaching

VitalCore: VitalCore Pharmacy – VitalCore Pharmacy

buy antibiotics for tooth infection antibiotics over the counter buy antibiotics for tooth infection

TrueMeds: pharmacy delivery – TrueMeds Pharmacy

VitalCore: best ed medication online – VitalCore Pharmacy

precription drugs from canada TrueMeds Pharmacy TrueMeds Pharmacy

https://vitalcorepharm.shop/# VitalCore

buy antibiotics: ClearMeds – buy antibiotics

VitalCore: ed pills – online prescription for ed

buy antibiotics online ClearMeds Pharmacy buy antibiotics

antibiotics over the counter: cheap antibiotics – buy antibiotics

cheap canadian pharmacy: TrueMeds Pharmacy – TrueMeds

https://truemedspharm.com/# buying drugs from canada

buy antibiotics online ClearMeds Pharmacy buy antibiotics online for uti

daftar garuda888 mudah dan cepat: garuda888 slot online terpercaya – agen garuda888 bonus new member

casino online sicuri con Starburst: Starburst slot online Italia – starburst

starburst jackpot e vincite su Starburst Italia giocare a Starburst gratis senza registrazione

link alternatif garuda888 terbaru: link alternatif garuda888 terbaru – situs judi online resmi Indonesia

jackpot e vincite su Starburst Italia: Starburst giri gratis senza deposito – migliori casino online con Starburst

http://1wstarburst.com/# bonus di benvenuto per Starburst

bonaslot jackpot harian jutaan rupiah 1wbona bonaslot link resmi mudah diakses

daftar garuda888 mudah dan cepat: daftar garuda888 mudah dan cepat – permainan slot gacor hari ini

Starburst giri gratis senza deposito: starburst – starburst

bonaslot login: 1wbona – bonaslot login

barcatoto login

bonus di benvenuto per Starburst: Starburst giri gratis senza deposito – Starburst giri gratis senza deposito

https://1win888indonesia.com/# garuda888 live casino Indonesia

bonaslot 1wbona bonaslot link resmi mudah diakses

1win69: preman69 situs judi online 24 jam – preman69 slot

Book of Ra Deluxe slot online Italia: migliori casino online con Book of Ra – recensioni Book of Ra Deluxe slot

link alternatif garuda888 terbaru permainan slot gacor hari ini 1win888indonesia

bonus di benvenuto per Starburst: migliori casino online con Starburst – Starburst giri gratis senza deposito

preman69 login tanpa ribet: preman69 – preman69 slot

http://1wbook.com/# Book of Ra Deluxe soldi veri

migliori casino online con Starburst Starburst giri gratis senza deposito giocare da mobile a Starburst

Book of Ra Deluxe slot online Italia: bonus di benvenuto per Book of Ra Italia – recensioni Book of Ra Deluxe slot

bonaslot situs bonus terbesar Indonesia: bonaslot login – bonaslot jackpot harian jutaan rupiah

pharmacy website india: BharatMeds Direct – online shopping pharmacy india

BorderMeds Express prescription drugs mexico pharmacy BorderMeds Express

https://bordermedsexpress.com/# mexican pharmaceuticals online

free spins no deposit chukchansi casino age –

Jorg – united kingdom 2021,

bingo canada login and bonausaa slot volatility, or online

gambling in the uk

mexico drug stores pharmacies: BorderMeds Express – BorderMeds Express

online pharmacy india: п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india – indian pharmacy online

cheap mexican pharmacy п»їmexican pharmacy buy antibiotics from mexico

online pharmacy india: reputable indian online pharmacy – BharatMeds Direct

Tofranil: MapleMeds Direct – accurate rx pharmacy

reputable indian online pharmacy BharatMeds Direct top 10 pharmacies in india

https://maplemedsdirect.com/# clindamycin people’s pharmacy

BorderMeds Express: BorderMeds Express – medicine in mexico pharmacies

п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india: india pharmacy mail order – BharatMeds Direct

buy prescription drugs from india BharatMeds Direct indian pharmacy online

Tron Staking

MapleMeds Direct: rite aid pharmacy store – ralphs pharmacy

https://maplemedsdirect.shop/# MapleMeds Direct

BorderMeds Express buy kamagra oral jelly mexico BorderMeds Express

ton staking

ton staking

Online medicine order: pharmacy website india – best india pharmacy

mexican rx online: BorderMeds Express – BorderMeds Express

aetna online pharmacy: ribavirin online pharmacy – MapleMeds Direct

http://maplemedsdirect.com/# MapleMeds Direct

walgreen online pharmacy: asda pharmacy ventolin inhalers – MapleMeds Direct

BharatMeds Direct BharatMeds Direct best online pharmacy india

BharatMeds Direct: BharatMeds Direct – BharatMeds Direct

SpookySwap

BharatMeds Direct: BharatMeds Direct – BharatMeds Direct

https://bharatmedsdirect.shop/# indian pharmacy paypal

MapleMeds Direct MapleMeds Direct french pharmacy online

amoxicillin mexico online pharmacy: buy cialis from mexico – BorderMeds Express

Tron Staking

pillole per erezioni fortissime: Potenza Facile – viagra online spedizione gratuita

le migliori pillole per l’erezione viagra online Italia viagra consegna in 24 ore pagamento alla consegna

comprare farmaci online all’estero: kamagra originale e generico online – farmacie online sicure

http://farmacidiretti.com/# Farmacia online miglior prezzo

farmacia online senza ricetta kamagra oral jelly spedizione discreta farmacie online autorizzate elenco

migliori farmacie online 2024: kamagra originale e generico online – farmacie online sicure

п»їFarmacia online migliore: ForzaIntima – farmacia online

exchange USDT in Osaka

acquistare farmaci senza ricetta: acquisto discreto di medicinali in Italia – acquistare farmaci senza ricetta

comprare farmaci online all’estero Farmaci Diretti comprare farmaci online all’estero

viagra generico recensioni: Potenza Facile – viagra ordine telefonico

Tron Staking

https://potenzafacile.com/# viagra online spedizione gratuita

Farmacia online piГ№ conveniente: cialis online Italia – farmacia online senza ricetta

comprare farmaci online con ricetta farmacia italiana affidabile online farmacia online

Farmacia online migliore: tadalafil 10mg 20mg disponibile online – comprare farmaci online con ricetta

Tron Staking

Tron Staking

pillole per erezione in farmacia senza ricetta: viagra online Italia – viagra subito

https://pillolesubito.com/# Farmacie on line spedizione gratuita

acquistare farmaci senza ricetta trattamenti per la salute sessuale senza ricetta farmacia online piГ№ conveniente

viagra online in 2 giorni: viagra generico a basso costo – viagra pfizer 25mg prezzo

how to sell USDT in Japan

AI crypto sentiment analysis

3Commas bot strategy

FertiCare Online where can i buy clomid can i purchase cheap clomid without rx

crypto passive income Fantom

crypto trading bot profitability

algorithmic crypto trading

https://ferticareonline.com/# FertiCare Online

CardioMeds Express: lasix generic name – CardioMeds Express

crypto trading bot for market making

convert USDT in Dallas

automated DCA bot crypto

AML/KYC crypto USA

prednisone without prescription 10mg SteroidCare Pharmacy SteroidCare Pharmacy

ivermectin sensitivity in dogs: ivermectin toxicity in dogs – IverGrove

https://steroidcarepharmacy.com/# prednisone 5mg daily

oral ivermectin for chickens: IverGrove – ivermectin for goats

FertiCare Online FertiCare Online FertiCare Online

ivermectin news: ivermectin cost canada – IverGrove

p2p USDT Florida

where to exchange Tether in Venice

buy and sell crypto Maldives

trade USDT in Alexandria

best crypto exchange Ireland

TrustedMeds Direct: TrustedMeds Direct – amoxicillin 250 mg capsule

prednisone 60 mg tablet: 54 prednisone – buy prednisone without prescription

https://cardiomedsexpress.com/# lasix medication

furosemide 40 mg: lasix furosemide – lasix for sale

ivermectin pour on for cattle: ivermectin for horses – stromectol tablets buy online

Convert USDT to cash Las Vegas

p2p USDT Carrefour

togelon login

Ziatogel

top 10 online casinos ontario

furosemide 40mg: lasix uses – lasix furosemide

Ziatogel

jama ivermectin: ivermectin for goats lice – ivermectin for mini pigs

CardioMeds Express generic lasix furosemide 40 mg

IverGrove: IverGrove – IverGrove

FertiCare Online: FertiCare Online – where can i get cheap clomid no prescription

Koitoto

convert USDT in San Jose

Exchange Tether for cash San Francisco

Kamagra reviews from US customers: Fast-acting ED solution with discreet packaging – Men’s sexual health solutions online

https://sildenapeak.shop/# SildenaPeak

Men’s sexual health solutions online Fast-acting ED solution with discreet packaging Kamagra reviews from US customers

Kamagra oral jelly USA availability: ED treatment without doctor visits – Sildenafil oral jelly fast absorption effect

trade USDT in Brisbane

Non-prescription ED tablets discreetly shipped: Kamagra reviews from US customers – Sildenafil oral jelly fast absorption effect

dingdongtogel login

convert USDT BEP20 in Switzerland

cialis using paypal in australia: Tadalify – cialis over the counter

medyumlar

Kamagra reviews from US customers: KamaMeds – Fast-acting ED solution with discreet packaging

SildenaPeak viagra germany SildenaPeak

Tadalify: cialis 20 mg – Tadalify

https://tadalify.com/# Tadalify

ED treatment without doctor visits: Men’s sexual health solutions online – ED treatment without doctor visits

cialis street price where to buy cialis tadalafil 10mg side effects

medyumlar

Tadalify: Tadalify – Tadalify

Tadalify: Tadalify – Tadalify

Linetogel

cialis dose: Tadalify – Tadalify

Fast-acting ED solution with discreet packaging Non-prescription ED tablets discreetly shipped Affordable sildenafil citrate tablets for men

Tadalify: Tadalify – Tadalify

http://sildenapeak.com/# viagra discounts

trade USDT in Valencia

sildenafil 100mg cost: SildenaPeak – SildenaPeak

sell USDT for cash in Vienna

Kamagra oral jelly USA availability Online sources for Kamagra in the United States Men’s sexual health solutions online

ED treatment without doctor visits: Compare Kamagra with branded alternatives – Non-prescription ED tablets discreetly shipped

cialis 5mg daily how long before it works: Tadalify – cialis generic purchase

Affordable sildenafil citrate tablets for men: Kamagra reviews from US customers – Affordable sildenafil citrate tablets for men

https://sildenapeak.com/# cost of viagra prescription

Safe access to generic ED medication: Sildenafil oral jelly fast absorption effect – Affordable sildenafil citrate tablets for men

cheap viagra generic best price best viagra for sale SildenaPeak

cialis online aust: Tadalify – Tadalify

Asian4d

KamaMeds: Men’s sexual health solutions online – Affordable sildenafil citrate tablets for men

Kamagra oral jelly USA availability Kamagra reviews from US customers Sildenafil oral jelly fast absorption effect

SildenaPeak: buy viagra online nz – SildenaPeak

http://sildenapeak.com/# SildenaPeak

cheapest generic viagra prices: can you buy viagra over the counter canada – sildenafil mexico cheapest

Goltogel

Danatoto

Goltogel

Online sources for Kamagra in the United States Men’s sexual health solutions online Online sources for Kamagra in the United States

shiokambing2

SildenaPeak: SildenaPeak – generic viagra price canada

cialis trial pack: Tadalify – cialis 100mg from china

SildenaPeak SildenaPeak generic viagra 150 mg pills

SildenaPeak: SildenaPeak – SildenaPeak

http://kamameds.com/# Men’s sexual health solutions online

where can i find viagra: SildenaPeak – sildenafil 50mg tablets coupon

Tadalify: Tadalify – Tadalify

dapoxetine and tadalafil: tadalafil and sildenafil taken together – Tadalify

SildenaPeak: SildenaPeak – SildenaPeak

http://sildenapeak.com/# SildenaPeak

cialis lower blood pressure cialis effect on blood pressure Tadalify

ED treatment without doctor visits: ED treatment without doctor visits – Fast-acting ED solution with discreet packaging

cialis online pharmacy: Tadalify – cialis indications

Safe access to generic ED medication: Non-prescription ED tablets discreetly shipped – Safe access to generic ED medication

Sell My House Fast in Tampa, FL

viagra online united states: SildenaPeak – 200 mg viagra

Pokerace99

http://kamameds.com/# Online sources for Kamagra in the United States

SildenaPeak: SildenaPeak – SildenaPeak

KamaMeds: ED treatment without doctor visits – KamaMeds

SildenaPeak SildenaPeak viagra pill otc

SildenaPeak: SildenaPeak – prices for viagra

SildenaPeak: viagra for sale in us – SildenaPeak

https://sildenapeak.com/# SildenaPeak

Fast-acting ED solution with discreet packaging Non-prescription ED tablets discreetly shipped Compare Kamagra with branded alternatives

Gametoto

Mexican Pharmacy Hub: buy viagra from mexican pharmacy – order kamagra from mexican pharmacy

mexico drug stores pharmacies: Mexican Pharmacy Hub – Mexican Pharmacy Hub

Asian4d

publix pharmacy amoxicillin: best online pharmacy ativan – osco pharmacy store locator

best india pharmacy reputable indian online pharmacy Online medicine order

reputable indian online pharmacy: best india pharmacy – Indian Meds One

Gametoto

Saudaratoto

http://medidirectusa.com/# MediDirect USA

Sell My House Fast in Tampa, FL

injection moulding tool material

Mexican Pharmacy Hub: legit mexican pharmacy for hair loss pills – safe mexican online pharmacy

Pokerace99

MediDirect USA: femara online pharmacy – seroquel xr online pharmacy

Mexican Pharmacy Hub Mexican Pharmacy Hub Mexican Pharmacy Hub

crypto bank transfer Turkey

Indian Meds One: Indian Meds One – indian pharmacy paypal

MediDirect USA: amlodipine pharmacy prices – why is zyrtec d behind the pharmacy counter

Zyloprim MediDirect USA MediDirect USA

nortriptyline online pharmacy: MediDirect USA – MediDirect USA

https://mexicanpharmacyhub.shop/# Mexican Pharmacy Hub

swap USDT in Heraklion

exchange USDT in Riyadh

how to sell USDT in Rome

swap USDT in Hilo

world pharmacy india: Indian Meds One – Indian Meds One

exchange USDT in Abu Dhabi

motilium inhouse pharmacy MediDirect USA cheap pharmacy no prescription

exchange USDT in Lisbon

Indian Meds One: Indian Meds One – Indian Meds One

sell USDT in Mdina

convert USDT to EUR in Cyprus

swap USDT in Jakarta

Sell USDT in Vancouver

Mexican Pharmacy Hub: rybelsus from mexican pharmacy – amoxicillin mexico online pharmacy

http://medidirectusa.com/# MediDirect USA

Mexican Pharmacy Hub: Mexican Pharmacy Hub – Mexican Pharmacy Hub

Prodaja USDT Split

pharmacy dispensing clozapine MediDirect USA MediDirect USA

Crypto exchange near me Nice

Exchange USDT for cash Copenhagen

OTC crypto desk Antwerp

pharmacy bangkok viagra: cialis online pharmacy australia – MediDirect USA

world pharmacy india: top 10 pharmacies in india – Indian Meds One

What are the fees for selling USDT in Germany?

Ta ut USDT i kontanter

wall drug store: MediDirect USA – MediDirect USA

Sell USDT in Belgrade

united pharmacy fincar MediDirect USA MediDirect USA

This is a great piece of content marketing. Well done to whoever wrote this.

Sell USDT for Kronor in Stockholm

https://medidirectusa.shop/# vips pharmacy viagra

MediDirect USA: MediDirect USA – wellbutrin pharmacy online

Malibu USDT to cash

Vendre crypto sans vérification Monaco

crypto exchange madrid with low fees

Mexican Pharmacy Hub: trusted mexico pharmacy with US shipping – Mexican Pharmacy Hub

best crypto cash out options in turkey

Get cash for USDT El Poblado

Vender Tether em Lisboa

One thing I love about Frax Swap is the transparency of their transactions.

Mexican Pharmacy Hub Mexican Pharmacy Hub zithromax mexican pharmacy

india pharmacy mail order: Indian Meds One – Indian Meds One

low cost mexico pharmacy online: Mexican Pharmacy Hub – buy from mexico pharmacy

http://mexicanpharmacyhub.com/# Mexican Pharmacy Hub

top 10 pharmacies in india: Indian Meds One – india pharmacy mail order

It’s the combination of speed, low cost, and a great user experience that makes SpiritSwap my #1 DEX on the Fantom network.

Promo slot gacor hari ini: Situs judi resmi berlisensi – Situs judi resmi berlisensi

Swerte99 casino Swerte99 casino Swerte99 login

The section on checking the token contract address is a crucial security tip.

Slot gacor hari ini: Bonus new member 100% Mandiribet – Link alternatif Mandiribet

Bandar bola resmi: Promo slot gacor hari ini – Link alternatif Beta138

Live casino Mandiribet Mandiribet Mandiribet login

https://mandiwinindo.site/# Mandiribet

Jiliko slots: maglaro ng Jiliko online sa Pilipinas – Jiliko bonus

Jiliko casino: Jiliko casino walang deposit bonus para sa Pinoy – Jiliko app

jilwin maglaro ng Jiliko online sa Pilipinas Jiliko slots

Uduslar? tez c?xar Pinco il?: Slot oyunlar? Pinco-da – Kazino bonuslar? 2025 Az?rbaycan

How to sell USDT in Buenos Aires

Online casino Jollibet Philippines: Online betting Philippines – 1winphili

Swerte99 casino Swerte99 app Swerte99 app

Slot gacor Beta138: Slot gacor Beta138 – Bandar bola resmi

https://1winphili.company/# Online casino Jollibet Philippines

Kimliksiz USDT satmak Türkiye

indotogel login

get idr for tether trc-20 bali

Swerte99 login Swerte99 online gaming Pilipinas Swerte99 app

Bandar togel resmi Indonesia: Abutogel login – Link alternatif Abutogel

get usd cash for tether trc-20 buenos aires

Jiliko: Jiliko app – maglaro ng Jiliko online sa Pilipinas

Jackpot togel hari ini: Bandar togel resmi Indonesia – Link alternatif Abutogel

Slot gacor Beta138 Promo slot gacor hari ini Promo slot gacor hari ini

https://1winphili.company/# jollibet app

Bandar bola resmi: Bonus new member 100% Beta138 – Withdraw cepat Beta138

Jiliko login: Jiliko – maglaro ng Jiliko online sa Pilipinas

Swerte99 app Swerte99 online gaming Pilipinas Swerte99 casino

Rut ti?n nhanh GK88: Khuy?n mai GK88 – Dang ky GK88

Link vào GK88 m?i nh?t: Trò choi n? hu GK88 – Trò choi n? hu GK88

Casino online GK88 Dang ky GK88 GK88

Swerte99 app: Swerte99 online gaming Pilipinas – Swerte99 app

jollibet app: jollibet app – jollibet casino

https://gkwinviet.company/# Nha cai uy tin Vi?t Nam

jollibet app: jollibet login – Online betting Philippines

bk8 login

Online gambling platform Jollibet Online betting Philippines jollibet app

Mandiribet: Situs judi resmi berlisensi – Situs judi online terpercaya Indonesia

Dang ky GK88: GK88 – Slot game d?i thu?ng

swap tron wallet

Link alternatif Mandiribet: Bonus new member 100% Mandiribet – Situs judi resmi berlisensi

Hand Sanitisers

https://jilwin.pro/# Jiliko casino walang deposit bonus para sa Pinoy

jollibet login 1winphili Jollibet online sabong

best crypto cash out options in spainSell USDT in Barcelona

Hand Dryers

IverCare Pharmacy: ivermectin dog dose – ivermectin apple flavored horse paste

http://fluidcarepharmacy.com/# FluidCare Pharmacy

AsthmaFree Pharmacy: AsthmaFree Pharmacy – AsthmaFree Pharmacy

tron bridge

liquid ivermectin dosage for humans: ivermectin discovery – IverCare Pharmacy

IverCare Pharmacy: ivermectin sheep drench for dogs – IverCare Pharmacy

best time to take semaglutide AsthmaFree Pharmacy what is semaglutide

FluidCare Pharmacy: lasix side effects – FluidCare Pharmacy

RelaxMedsUSA: RelaxMedsUSA – muscle relaxants online no Rx

ivermectin medicine IverCare Pharmacy ivermectin inflammation

goltogel

http://asthmafreepharmacy.com/# AsthmaFree Pharmacy

lasix 40mg: lasix 100mg – lasix pills

IverCare Pharmacy: ivermectin pills for humans – ivermectin dosage chart for dogs

ivermectin overdose in humans: how to take ivermectin for scabies – IverCare Pharmacy

AsthmaFree Pharmacy: ventolin pharmacy uk – ventolin 200 mcg

how does semaglutide help you lose weight: online semaglutide gomedidirect.com – rybelsusВ®

semaglutide near me AsthmaFree Pharmacy AsthmaFree Pharmacy

totojitu login

cheap muscle relaxer online USA: affordable Zanaflex online pharmacy – Tizanidine 2mg 4mg tablets for sale

ivermectin sheep drench for dogs: stromectol prices – IverCare Pharmacy

https://fluidcarepharmacy.shop/# lasix side effects

how long does it take ivermectin to kill scabies merck ivermectin IverCare Pharmacy

artistoto

is compounded semaglutide going away: AsthmaFree Pharmacy – is semaglutide the same as tirzepatide

cost of ventolin in usa: AsthmaFree Pharmacy – buy ventolin online australia

buy furosemide online lasix 40mg FluidCare Pharmacy

lasix online: FluidCare Pharmacy – FluidCare Pharmacy

AsthmaFree Pharmacy: AsthmaFree Pharmacy – AsthmaFree Pharmacy

https://relaxmedsusa.com/# buy Zanaflex online USA

Mariatogel

how much is a ventolin ventolin online united states ventolin cream

buy Zanaflex online USA: prescription-free muscle relaxants – prescription-free muscle relaxants

Mariatogel

buy ventolin over the counter australia AsthmaFree Pharmacy buy ventolin online cheap

cheapest ventolin online uk: ventolin 4mg – ventolin 250 mcg

safe online source for Tizanidine: relief from muscle spasms online – RelaxMedsUSA

FluidCare Pharmacy furosemide 100 mg furosemida 40 mg

http://fluidcarepharmacy.com/# lasix pills

Dolantogel

lasix 40 mg: FluidCare Pharmacy – FluidCare Pharmacy

furosemide 40mg: FluidCare Pharmacy – FluidCare Pharmacy

AsthmaFree Pharmacy cheap ventolin inhaler AsthmaFree Pharmacy

Tizanidine tablets shipped to USA: relief from muscle spasms online – Zanaflex medication fast delivery

where can i buy stromectol ivermectin ivermectin injectable dosage for horses ivermectin cattle

FluidCare Pharmacy: lasix 100mg – FluidCare Pharmacy

Bosstoto

https://fluidcarepharmacy.shop/# furosemida 40 mg

AsthmaFree Pharmacy: AsthmaFree Pharmacy – generic ventolin inhaler

ventolin prescription online AsthmaFree Pharmacy AsthmaFree Pharmacy

ivermectin for cats fleas: IverCare Pharmacy – IverCare Pharmacy

AsthmaFree Pharmacy: AsthmaFree Pharmacy – AsthmaFree Pharmacy

cost of ivermectin pill ivermectin price buy ivermectin for dogs

can i buy ventolin over the counter in usa: AsthmaFree Pharmacy – ventolin prices

https://glucosmartrx.com/# AsthmaFree Pharmacy

ventolin buy canada AsthmaFree Pharmacy ventolin 6.7g

AsthmaFree Pharmacy: is rybelsus approved for weight loss – AsthmaFree Pharmacy

semaglutide drugs: what does compounded semaglutide mean – AsthmaFree Pharmacy

rybelsus patient assistance program rybelsus indication AsthmaFree Pharmacy

gengtoto login

http://relaxmedsusa.com/# trusted pharmacy Zanaflex USA

IndiGenix Pharmacy: IndiGenix Pharmacy – IndiGenix Pharmacy

CanadRx Nexus: CanadRx Nexus – CanadRx Nexus

batman138

my canadian pharmacy reviews: CanadRx Nexus – CanadRx Nexus

Online medicine home delivery: india pharmacy – IndiGenix Pharmacy

IndiGenix Pharmacy IndiGenix Pharmacy india online pharmacy

barcatoto

IndiGenix Pharmacy: best india pharmacy – buy medicines online in india

CanadRx Nexus: CanadRx Nexus – onlinecanadianpharmacy 24

gabapentin mexican pharmacy MexiCare Rx Hub MexiCare Rx Hub

udintogel login

MexiCare Rx Hub: buy cheap meds from a mexican pharmacy – MexiCare Rx Hub

buy kamagra oral jelly mexico legit mexican pharmacy without prescription MexiCare Rx Hub

MexiCare Rx Hub: п»їmexican pharmacy – MexiCare Rx Hub

top 10 pharmacies in india: best online pharmacy india – cheapest online pharmacy india

canada pharmacy world: CanadRx Nexus – CanadRx Nexus

https://mexicarerxhub.shop/# mexican rx online

Kepritogel

indianpharmacy com: IndiGenix Pharmacy – buy prescription drugs from india

Sbototo

reliable canadian pharmacy CanadRx Nexus CanadRx Nexus

MexiCare Rx Hub: MexiCare Rx Hub – buy viagra from mexican pharmacy

Hometogel

MexiCare Rx Hub rybelsus from mexican pharmacy safe mexican online pharmacy

indian pharmacy online: IndiGenix Pharmacy – IndiGenix Pharmacy

prescription drugs mexico pharmacy: MexiCare Rx Hub – buy cialis from mexico

jonitogel

http://indigenixpharm.com/# IndiGenix Pharmacy

the canadian drugstore CanadRx Nexus CanadRx Nexus

MexiCare Rx Hub: semaglutide mexico price – buy antibiotics from mexico

generic drugs mexican pharmacy: MexiCare Rx Hub – MexiCare Rx Hub

frax swap staking

MexiCare Rx Hub MexiCare Rx Hub buy kamagra oral jelly mexico

CanadRx Nexus: CanadRx Nexus – CanadRx Nexus

best india pharmacy: IndiGenix Pharmacy – top online pharmacy india

mantcha swap yield farming

http://indigenixpharm.com/# mail order pharmacy india

indian pharmacies safe: reputable indian online pharmacy – indian pharmacy paypal

CanadRx Nexus CanadRx Nexus CanadRx Nexus

Hometogel

legit mexican pharmacy without prescription: MexiCare Rx Hub – buy meds from mexican pharmacy

india pharmacy: IndiGenix Pharmacy – best india pharmacy

sildenafil mexico online MexiCare Rx Hub MexiCare Rx Hub

DefiLlama

buy kamagra oral jelly mexico: isotretinoin from mexico – buy antibiotics from mexico

https://canadrxnexus.shop/# canadian pharmacies

IndiGenix Pharmacy: IndiGenix Pharmacy – best india pharmacy

IndiGenix Pharmacy IndiGenix Pharmacy IndiGenix Pharmacy

IndiGenix Pharmacy: IndiGenix Pharmacy – IndiGenix Pharmacy

indian pharmacy: online pharmacy india – best india pharmacy

canadian pharmacy scam onlinecanadianpharmacy 24 CanadRx Nexus

prednisone 40 mg tablet: anti-inflammatory steroids online – order corticosteroids without prescription

https://reliefmedsusa.com/# buy prednisone tablets online

Bos88

cost of clomid prices: Clomid Hub Pharmacy – Clomid Hub Pharmacy

NeuroRelief Rx gabapentin controlled drug can you take vitamin d with gabapentin

Bandartogel77

matcha swap

anti-inflammatory steroids online: prednisone price canada – Relief Meds USA

Relief Meds USA: prednisone 10mg prices – prednisone generic brand name

NeuroRelief Rx NeuroRelief Rx NeuroRelief Rx

anti-inflammatory steroids online: order corticosteroids without prescription – Relief Meds USA

affordable Modafinil for cognitive enhancement: where to buy Modafinil legally in the US – Modafinil for focus and productivity

http://clearmedsdirect.com/# Clear Meds Direct

NeuroRelief Rx can you freebase gabapentin replacement drug for gabapentin

cost of prednisone tablets: prednisone 250 mg – anti-inflammatory steroids online

Mantle Bridge

order corticosteroids without prescription: Relief Meds USA – order corticosteroids without prescription

NeuroRelief Rx NeuroRelief Rx gabapentin charley horse

Anyswap

antibiotic treatment online no Rx: low-cost antibiotics delivered in USA – ClearMeds Direct

anti-inflammatory steroids online cheap prednisone online no prescription online prednisone

Frax Swap

https://reliefmedsusa.com/# ReliefMeds USA

NeuroRelief Rx: NeuroRelief Rx – gabapentin pbs cost

antibiotic treatment online no Rx Clear Meds Direct amoxicillin online pharmacy

ReliefMeds USA: prednisone prices – order corticosteroids without prescription

Togelup

gabapentin 300 and methylcobalamin tablets NeuroRelief Rx gabapentin sr tablets

https://clomidhubpharmacy.shop/# cost of clomid pills

gabapentin and phenibut combo: gabapentin controlled drug – gabapentin 300mg prospect

Aw8

how can i get cheap clomid where to buy clomid online where to buy generic clomid for sale

ReliefMeds USA: Relief Meds USA – Relief Meds USA

Bk8

buy generic clomid without insurance: cost clomid pills – Clomid Hub Pharmacy

Bk8

can you buy prednisone Relief Meds USA 5 mg prednisone tablets

http://clearmedsdirect.com/# antibiotic treatment online no Rx

Clomid Hub: Clomid Hub Pharmacy – Clomid Hub Pharmacy

NeuroRelief Rx NeuroRelief Rx gabapentin price canada

anti-inflammatory steroids online: anti-inflammatory steroids online – generic prednisone pills

NeuroRelief Rx: gabapentin for vicodin withdrawal – can you get fluoxetine

amoxicillin price canada order amoxicillin without prescription order amoxicillin without prescription

http://clomidhubpharmacy.com/# clomid order

Clear Meds Direct: 875 mg amoxicillin cost – low-cost antibiotics delivered in USA

anti-inflammatory steroids online: order corticosteroids without prescription – ReliefMeds USA

where to buy amoxicillin 500mg low-cost antibiotics delivered in USA Clear Meds Direct

NeuroRelief Rx: NeuroRelief Rx – does gabapentin increase dopamine

Relief Meds USA: prednisone without prescription – Relief Meds USA

https://clomidhubpharmacy.shop/# can i get clomid

Cialis without prescription buy Cialis online cheap cheap Cialis Canada

compare lexapro prices: Lexapro for depression online – buy lexapro online without prescription

buy cheap propecia without insurance: propecia order – Propecia for hair loss online

generic Finasteride without prescription: generic propecia prices – Finasteride From Canada

https://lexapro.pro/# Lexapro for depression online

cheap Accutane: purchase generic Accutane online discreetly – isotretinoin online

cheap Propecia Canada: order cheap propecia pill – Propecia for hair loss online

cheap Cialis Canada: tadalafil online no rx – Tadalafil From India

https://finasteridefromcanada.shop/# Propecia for hair loss online

generic sertraline buy Zoloft online without prescription USA Zoloft Company

lexapro online: Lexapro for depression online – lexapro brand name in india

Finasteride From Canada: cost cheap propecia online – generic Finasteride without prescription

generic isotretinoin purchase generic Accutane online discreetly Accutane for sale

generic isotretinoin: Accutane for sale – Accutane for sale

Accutane for sale: Isotretinoin From Canada – cheap Accutane

cost of cheap propecia online Propecia for hair loss online cheap Propecia Canada

http://finasteridefromcanada.com/# Propecia for hair loss online

Tadalafil From India: Cialis without prescription – tadalafil online no rx

isotretinoin online: USA-safe Accutane sourcing – order isotretinoin from Canada to US

Base Bridge

defillama swap

Lexapro for depression online: Lexapro for depression online – Lexapro for depression online

defillama

generic Cialis from India: Cialis without prescription – tadalafil 10mg generic

https://lexapro.pro/# Lexapro for depression online

Zoloft for sale buy Zoloft online buy Zoloft online

cheap Cialis Canada: Cialis without prescription – tadalafil online no rx

cost cheap propecia price: Propecia for hair loss online – generic Finasteride without prescription

Lexapro for depression online Lexapro for depression online Lexapro for depression online

compare lexapro prices: lexapro 10 mg tablet – Lexapro for depression online

defillama yield farming

defillama tvl

Lexapro for depression online: Lexapro for depression online – Lexapro for depression online

https://lexapro.pro/# Lexapro for depression online

manta swap

manta swap

defillama token

Propecia for hair loss online Finasteride From Canada Finasteride From Canada

lexapro 50 mg: prescription price for lexapro – lexapro medication

Finasteride From Canada: generic Finasteride without prescription – Finasteride From Canada

Lexapro for depression online buy lexapro australia Lexapro for depression online

bridge wormhole

cheap Accutane: buy Accutane online – isotretinoin online

buy Accutane online: cheap Accutane – generic isotretinoin

https://isotretinoinfromcanada.shop/# generic isotretinoin

Propecia for hair loss online Propecia for hair loss online Finasteride From Canada

Zoloft for sale: sertraline online – Zoloft Company

real online pokies in united states, casino paypal deposit usa and best new casino nz, or best online poker in united states

my website :: bingo caller software for mac (Emil)

Transparent fee structure and gas‑optimized for cost efficiency.

generic Cialis from India Cialis without prescription generic Cialis from India

buying cheap propecia without a prescription: order generic propecia without rx – Finasteride From Canada

Transparent fee structure and gas‑optimized for cost efficiency.

buy Zoloft online: buy Zoloft online without prescription USA – buy Zoloft online without prescription USA

http://finasteridefromcanada.com/# Finasteride From Canada

Finasteride From Canada generic Finasteride without prescription propecia pills

generic isotretinoin: Accutane for sale – Isotretinoin From Canada

Tadalafil From India: cheap Cialis Canada – Cialis without prescription

Supports ETH, USDT, USDC, MANTA and more tokens.

Lexapro for depression online lexapro 20 mg tablet lexapro prescription

cheap Zoloft: Zoloft Company – Zoloft Company

Isotretinoin From Canada: isotretinoin online – Accutane for sale

https://zoloft.company/# cheap Zoloft

Supports ETH, USDT, USDC, MANTA and more tokens.

buy Cialis online cheap Cialis without prescription generic Cialis from India

lexapro discount: buy lexapro no prescription – п»їlexapro

generic Finasteride without prescription: Finasteride From Canada – cheap Propecia Canada

purchase generic Zoloft online discreetly: purchase generic Zoloft online discreetly – buy Zoloft online

price comparison tadalafil buy tadalafil online paypal tadalafil online no rx

Zoloft Company: Zoloft Company – Zoloft Company

http://expresscarerx.org/# ExpressCareRx

top 10 pharmacies in india: IndiaMedsHub – IndiaMedsHub

best online pharmacy india IndiaMedsHub IndiaMedsHub

top 10 pharmacies in india: india online pharmacy – indian pharmacy paypal

target pharmacy ventolin: ExpressCareRx – ExpressCareRx

valacyclovir online pharmacy online pharmacy viagra cialis fluoxetine pharmacy

http://medimexicorx.com/# MediMexicoRx

india pharmacy mail order: IndiaMedsHub – buy prescription drugs from india

MediMexicoRx: MediMexicoRx – sildenafil mexico online

buy provigil online pharmacy peoples pharmacy best online pharmacy wellbutrin

MediMexicoRx: legit mexico pharmacy shipping to USA – MediMexicoRx

india online pharmacy: IndiaMedsHub – online pharmacy india

search rx pharmacy discount card: guardian pharmacy loratadine – ExpressCareRx

IndiaMedsHub IndiaMedsHub online shopping pharmacy india

http://expresscarerx.org/# no prescription required pharmacy

senior rx care pharmacy: viagra in dubai pharmacy – sam’s club pharmacy propecia

legit mexican pharmacy for hair loss pills: amoxicillin mexico online pharmacy – rybelsus from mexican pharmacy

generic drugs mexican pharmacy modafinil mexico online cheap mexican pharmacy

amoxicillin mexico online pharmacy: MediMexicoRx – best mexican pharmacy online

MediMexicoRx: buy antibiotics over the counter in mexico – zithromax mexican pharmacy

MediMexicoRx MediMexicoRx MediMexicoRx

https://expresscarerx.online/# ExpressCareRx

legit non prescription pharmacies: central rx pharmacy – ExpressCareRx

best online pharmacy india indian pharmacy online Online medicine home delivery

MediMexicoRx: buy from mexico pharmacy – MediMexicoRx

https://medimexicorx.com/# MediMexicoRx

uk pharmacy propecia naltrexone pharmacy online accutane online pharmacy reviews

gabapentin mexican pharmacy: order azithromycin mexico – isotretinoin from mexico

п»їlegitimate online pharmacies india: best online pharmacy india – online shopping pharmacy india

apotek på nätet sverige medicin apotek mäta blodtryck på apotek

pharmacy online netherlands: Medicijn Punt – medicatielijst apotheek

metylenblГҐtt apotek: Trygg Med – spyposer apotek

https://tryggmed.com/# paracetamol apotek

rosenrot apotek Trygg Med jernbane apotek

avfГёringspiller apotek: ansiktsvisir apotek – jobbe i apotek

varmebelte apotek: TryggMed – apotek ГҐpent kristi himmelfartsdag

bandasje apotek Trygg Med protein pulver apotek

rГҐdgivning apotek: apotek Г¶ronhГҐltagning – hemorrojder salva apotek

http://tryggmed.com/# alkotester apotek

destillert vann apotek Trygg Med promilletester apotek

medicijen: internetapotheek nederland – nieuwe pharma

ilningar engelska: fГ¶rkylning engelska – snabb hemleverans apotek

online apotheke Medicijn Punt apteka internetowa nl

pharmacy nl: MedicijnPunt – de apotheker

bestellen medicijnen: recept online – verzorgingsproducten apotheek

https://zorgpakket.shop/# online apotheek nederland met recept

apotek Г¶ppetider graviditetstest apotek ljusrosa mens

gravidpaket apotek: SnabbApoteket – apotek nГ¤tet

medicijen: medicijen – pharmacy nl

online medicatie bestellen MedicijnPunt mijn apotheek medicijnen

https://clinicagaleno.com/# blastoestimulina ovulos comprar sin receta

medebiotin fuerte se puede comprar sin receta: Clinica Galeno – farmacia online ffp3

https://clinicagaleno.com/# progeffik 200 farmacia online

inava 7/100 aciclovir sans ordonnance pharmacie prix neutrogena intense repair

artrotec 75 prezzo: OrdinaSalute – omeprazolo (20 mg prezzo)

https://clinicagaleno.shop/# flutox se puede comprar sin receta

https://pharmadirecte.com/# natrum muriaticum 5ch

quel anti-inflammatoire peut-on avoir par une pharmacie sans ordonnance ? anxiolitique sans ordonnance sildenafil acheter en ligne

farmacia online pamplona: farmacia dr max online shop – farmacia espanhola online

http://pharmadirecte.com/# xenical pharmacie sans ordonnance

se puede comprar amoxicilina sin receta: Clinica Galeno – comprar guantes farmacia online

https://pharmadirecte.com/# cialis 20 mg

https://ordinasalute.shop/# colecalciferolo 50000

viagra pharmacie sans ordonnance: anti inflammatoire en pharmacie sans ordonnance – huile precieuse caudalie

farmacia germania online ebastel forte se puede comprar sin receta donde comprar viagra original sin receta

https://ordinasalute.com/# ricette online farmacia

farmacia online viagra generico: Clinica Galeno – farmacia estudios online