Authors: Lars Nilsson, Thierry Beranger, Cristina Modoran, Charlotte Demuinjk and Dionysia Basta, Ana Norman and Thierry Beranger

Affiliated organization: European Commission

Type of publication: Report

Date of publication: March 2016

Introduction

The Economic Partnership Agreements (EPA) between the EU and the African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) states are the main element of the ACP-EU trade cooperation, and date back to the signing of the Cotonou Agreement in 2000. The objectives as set out in the Cotonou Agreement were to go beyond the unilateral preferential market access to the EU, which ACP countries had enjoyed since the first Lomé Convention in 1975, by:

– taking account of the different level of development between the negotiating parties.

– fostering the integration of the ACP states into the world economy,

– supporting their regional integration, and

– making trade a better tool for growth and sustainable development.

In order to negotiate EPAs, ACP states chose their own regional configurations, usually building upon existing economic integration processes. Seven regions resulted from that choice: five in Africa, one in the Caribbean and one in the Pacific. In December 2001, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Heads of State Summit decided that West Africa was to negotiate an EPA as a region. In October 2003, negotiations between West Africa (including Mauritania) and the EU were officially launched in Cotonou. On the West African side, the negotiating mandate was granted to the regional organisations (ECOWAS and West African Economic and Monetary Union-WAEMU).

After several rounds of negotiations spanned over more than 10 years, the negotiations were formally concluded on 6 February 2014 in Brussels and the agreement was initialled on 30 June 2014 in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso by the Chief Negotiators. The ECOWAS Summit in Accra on 10 July 2014 fully endorsed the EPA and decided that it should be signed and ratified. On the EU side, the Council Decision to sign and provisionally apply the EPA was adopted on 12 December 2014. Following the endorsement of the negotiated deal by both parties to the Agreement, it was presented for signature and will subsequently be submitted to the European Parliament for consent and to national Parliaments of signatory states for ratification.

Context and rationale for the West Africa – EU EPA

Towards the EPA Starting point of the EPA process: the Cotonou Agreement

The Lomé Conventions (the first of which dates back to 1975) set out the principle of non-reciprocal concessions on trade in favour of countries from Africa Caribbean and Pacific (ACP). The first three Conventions were concluded for a period of five years. The fourth Convention covered the period from 1990 to 2000.

By the end of the 1990s there was a sense of frustration that the significant trade preferences for ACP exports had failed to stem the steady fall in ACP countries’ share of total extra-EU imports and to bring the much needed diversification of ACP economies. Moreover, these preferences were in breach of the rules of the World Trade Organisation (WTO), which provide that countries in a similar situation should be treated on an equal basis. However, WTO rules also provide that countries can be granted specific treatment, insofar as such treatment is provided in the framework of a reciprocal free trade agreement that covers substantially all trade between the parties. The WTO agreed with much difficulty to an exception for the non-reciprocal trade regime until the end of 2007, after which they were to be replaced by WTO compatible arrangements.

The ACP countries and the EU have jointly designed the EPAs as a response to this commitment. Therefore the Cotonou Agreement foresaw the setting up of a new reciprocal – partnership for trade and development which maintained still a significant asymmetry in favour of ACP countries.

In 2003 and 2004, formal regional negotiations were launched with West Africa, Central Africa, Eastern and Southern Africa, the Caribbean, Southern Africa / SADC and the Pacific. Countries of the East African Community formed a separate negotiating group in August 2007. However, negotiations made slow progress and by the beginning of 2007 no WTO-compatible trade agreements had yet been agreed. In deference to the rapidly approaching end-of-year deadline, it was agreed in October 2007 to split the negotiations into two stages: (i) “interim EPAs” (also called “stepping stones”), to be concluded by the end of 2007; followed by (ii) further negotiations towards comprehensive EPAs to be concluded at the regional level.

Overview of the economic and trade relations between the EU and West Africa

West Africa’s economy

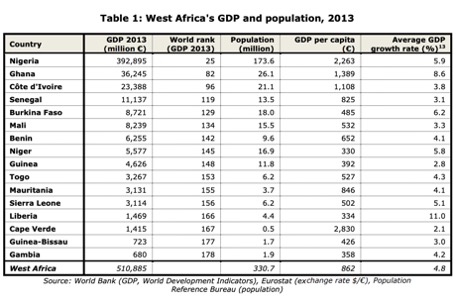

The 16 West African countries have a population of over 330 million, with over half of them in Nigeria. Their Gross Domestic Product (GDP) ranges from €680 million in Gambia to €36 billion in Ghana, with Nigeria reaching €393 billion in 2013. According to the United Nations categorisation, 12 out of the 16 countries are identified as LDCs. The remaining four countries (Cape Verde, Nigeria, Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire) are lower middle income countries.

In the 2008-2013 period, the average annual GDP growth rate was slightly below 5% for the 16 West African countries as a total, with the highest growth rate reported for Liberia (11%) and Ghana (9%) and the lowest for Cape Verde (2%). Nigeria is by far the largest economy in West Africa, representing 76.9% of West Africa’s GDP, followed by Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal. Collectively, those four countries amount to more than 90% of West Africa’s economy.

West Africa’s international competitiveness, determined by the institutional environment, infrastructure, the stability of the macroeconomic environment, quality of education, goods market and labour market efficiency, financial market development, technology and innovation, is poor. All the West African countries are ranked in the Global Competitiveness Index 2014-2015 below the 111th position (out of 144 economies), with Mauritania and Guinea being among the 5 worst performers.

In the World Bank’s 2015 Doing Business ranking15, West African countries are ranked below the 140 position (out of 189 countries), with the exception of Ghana (114) and Cape Verde (126). The average position of West African countries is 153, and the main issues identified are “getting electricity” (average rank 160/189), “paying taxes” (155/189), and “dealing with constriction permits” (143/189).

West Africa’s largest trading partner is the EU, which receives 35% of West Africa’s exports and accounts for 22% of West Africa’s imports. Other important trading partners are India, the US and China. In the last decade West African countries have increased both exports and imports to and from their key trading partners (with the exception of the US on the export side, mainly due to the decrease of Nigerian exports to the US, and South Korea on the import side).

Trade relations between the EU and West Africa

Trade in goods

In 2014, EU exports to West Africa stood at €31 billion, i.e. accounting for 2% of EU total exports to the world, and EU imports from West Africa measured over €37 billion, i.e. 2% of EU total imports – percentages which are comparable to those of India or Canada. From 2003 to 2010, EU exports to and imports from West Africa have increased at a similar rate (10% annual growth rate on average). However, since 2010, EU imports of West African goods have increased at a faster rate than EU exports to West Africa and remain significantly higher despite a decline in 2013 and 2014.

West Africa’s international competitiveness, determined by the institutional environment, infrastructure, the stability of the macroeconomic environment, quality of education, goods market and labour market efficiency, financial market development, technology and innovation, is poor. All the West African countries are ranked in the Global Competitiveness Index 2014-2015 below the 111th position (out of 144 economies), with Mauritania and Guinea being among the 5 worst performers

Five West African countries (Nigeria, Togo, Ghana, Senegal, and Côte d’Ivoire) account for 79% of EU exports to the region, with Nigeria receiving nearly 40% of EU exports to the region, Togo receiving 15%, and Ghana and Senegal about 10% each.

In terms of EU imports from West Africa, Nigeria is the EU’s main supplier from the region (76%), followed by Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana (9% and 8 % respectively).

Importance of trade by products

“Minerals” (i.e. oil) were the section most exported by the EU (above €11 billion, accounting for 37% of EU exports to West Africa) followed by machinery and vehicles (HS 16 and 17 – €5.7 and 2.5 billion respectively, accounting for 18% and 8% of EU’s exports to West Africa). EU exports of “minerals” to West Africa (mostly refined oil) are mainly directed to Togo (36% of EU’s exports of minerals to West Africa), Nigeria (33%), Ghana (11%) and Senegal (10%). Concerning machinery, 48% of EU exports to West Africa go to Nigeria and 10% each to Ghana and to Côte d’Ivoire.

West Africa’s tariff structure

Reflecting a significant step forward in West Africa’s history of regional integration, the Common External Tariff (CET) for ECOWAS was adopted in October 2013 in Dakar. Officially coming into effect on the 1 January 2015, the CET harmonises tariff rates amongst West African countries. Based on the tariff bands of the WAEMU CET (0%, 5%, 10%, 20%) and with the addition of a fifth band at 35%, the CET reflects the political decision to protect sensitive sectors and nascent industries from trade liberalisation.

West Africa’s largest trading partner is the EU, which receives 35% of West Africa’s exports and accounts for 22% of West Africa’s imports. Other important trading partners are India, the US and China. In the last decade West African countries have increased both exports and imports to and from their key trading partners (with the exception of the US on the export side, mainly due to the decrease of Nigerian exports to the US, and South Korea on the import side)

Before the CET, the tariff structures of the various countries were very diverse. In general, most tariffs at HS6 level were found between 3% and 20%, with the highest values recorded in arms and ammunition (HS 19) in Liberia and Cape Verde. The maximum tariffs applied (at 6-digit level) were around 30% in Nigeria and Sierra Leone. For the remaining West African countries, the maximum tariff was 20%.

Trade in services In terms of trade in services, West Africa’s exports to the world measured €8.3 billion in 2013, while their imports were €31.2 billion. Ghana and Nigeria are the largest exporters accounting each for 22% of total West Africa’s services exports to the world, followed by Senegal and Côte d’Ivoire (12% and 9% respectively). On the other hand, Nigeria is the major importer (54% of the total West Africa’s services imports from the world), followed by Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire (12% and 7% respectively). The majority of West African services that are exported to the world are transportation, travel and other business services.

West Africa’s exports to the EU reached €5.5 billion in 2013 and West Africa’s imports from the EU €9.5 billion (see Table 6). EU’s major trading partner in West Africa is Nigeria (accounting for 51% of EU exports and 30% of EU imports), followed by Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire (accounting for around 10% of exports/ imports each). West Africa represents about 1% of EU’s exports and imports in services.

The content of the West Africa – EU EPA

The EPA is based on the principles and essential elements of the Cotonou Agreement: equality of the partners, participation (including participation of civil society), enhanced dialogue (as reflected in the setting-up of joint institutions to monitor the implementation of the EPA), and regional integration. The essential elements referred to in the Cotonou Agreement are human rights, democratic principles and the rule of law, and good governance.

Five West African countries (Nigeria, Togo, Ghana, Senegal, and Côte d’Ivoire) account for 79% of EU exports to the region, with Nigeria receiving nearly 40% of EU exports to the region, Togo receiving 15%, and Ghana and Senegal about 10% each

Sustainable development is also a core objective of the agreement, covering human, cultural, economic, social, health and environmental interests. To reduce extreme poverty, the Parties agreed to design development cooperation projects aimed at promoting economic growth and intra-regional trade in West Africa, supporting sustainable forests and fisheries management, as well as adapting national administrations to trade liberalisation.

The EPA mainly covers trade in goods and development cooperation. This stems from a decision taken in 2009 by the Chief negotiators to split the negotiations between, on the one side, trade in goods and development cooperation, and, on the other side, the other domains such as trade in services or investment. This decision was mainly due to the time needed and lack of capacity to carry out a wide negotiation on all areas in parallel. However, as West Africa develops, West African economies will increasingly need services, research and innovation, rules on investment and competition, protection of intellectual property rights and personal data. Services such as transport, distribution or finance already significantly contribute to West Africa’s GDP growth. Those elements are also fundamental drivers for the competiveness of West African companies when it comes to trade in goods, and, to a large extent, constitute today a bottleneck for West Africa’s development.

Customs duties

The agreement takes account of the current differences in the level of development between the two regions and therefore weighs in West Africa’s favour with regard to tariff dismantling. The reduction of customs duties is a key aspect of the agreement and a key focus of the present study.

Exports to the EU

Products originating in West Africa (see rules of origin) shall be imported into the EU free of customs duties and quotas. This covers all products apart from arms and ammunitions. Quotas on sugar and sugar products can be imposed by the EU but only until 30 September 2015. Specific derogations are foreseen for sugar products and bananas exported to EU Outermost Regions, for a renewable period of 10 years.

The agreement replaces several trade schemes in force between the countries of the region (EBA, MAR, GSP+ and GSP). The immediate duty-free quota-free access to the EU market upon entry into force of the agreement will mostly benefit in the short term Nigeria and Cape Verde (respectively under GSP and GSP+). Other countries have already enjoyed free access to the EU market under the EBA and the MAR. It is worth recalling, however, that the MAR is a temporary scheme based on the parties’ willingness to enter into an EPA (i.e. without the EPA, the normal GSP would apply, not the MAR), and that the EBA is conditional on the LDC status (i.e. without the EPA, if a country “graduates” from LDC to middle-income status, the EBA’s benefit would be terminated after a transitory period34 and normal GSP would apply, not the EBA anymore). The EPA therefore not only harmonises the different regimes across the region, but it also provides certainty to all West African countries and businesses that the duty-free quota-free access to the EU market for their product will remain over time.

Imports from the EU

While the EU fully opens its market from the entry into force of the agreement, West Africa partially and progressively reduces and eliminates customs duty applicable to products originating in the European Union. This applies to 75% of tariff lines, and over a period of 20 years. In other words, 20 years after the entry into force of the EPA, 25% of tariff lines remain unchanged (all those at a 35% duty and about half of those at 20% duty).

Based on the five standard custom duties of 0%, 5%, 10%, 20% and 35% of the ECOWAS Common External Tariff (CET, see above), tariff lines were divided by West Africa negotiators into 4 categories depending on considerations such as the need for rapid access to intermediary products for local production purposes, basic population needs, etc.

In addition, the EPA includes several safeguards with a wide scope which can be deployed if imports of liberalised products are increasing too quickly thus jeopardising local markets. Special protection is foreseen for infant industries and for agricultural products. The EPA allows West Africa to take specific measures in case food security is threatened.

In terms of products, West Africa has excluded all the products which are considered most sensitive and currently face a 35% duty under the ECOWAS Common External Tariff (CET), such as meat (including poultry), yoghurt, eggs, processed meat, cocoa powder and chocolate, tomato paste and concentrate, soap and printed fabrics. Also excluded from liberalisation are half of the products currently attracting 20% duty under the ECOWAS CET such as fish and fish preparations, milk, butter and cheese, vegetables, flour, spirits, cement, paints, perfumes and cosmetics, stationery, textiles and apparel and fully built cars.

Movement of goods

Once in the territory of one of the parties (the EU or West Africa), goods shall move freely in the territory of the party without being subject to additional custom duties, in keeping with the objective of a customs union. West Africa is however granted a transitional period of 5 years in which to set up a free movement system. Cooperation is foreseen in the areas of fiscal reform and customs procedures.

Most favoured nation clause (“MFN clause”)

The most favoured nation (MFN) clause stipulates that the EU shall grant West Africa any more favourable tariff treatment that it grants to a third party. In a similar way, West Africa shall grant the EU any more favourable treatment that it would grant to a large industrial country (or group of countries). However, the MFN clause does not apply to preferential treatment granted by West Africa to countries of Africa or the ACP states, leaving the possibility, for instance, for further integration between African regions without any obligation to extend these preferences to the EU.

Trade defence instruments

The agreement sets out conditions for the use of trade defence instruments. Antidumping and compensatory measures are defined by way of reference to the relevant WTO Agreements. This is also the case for multilateral safeguard measures. Bilateral safeguard measures are allowed for a limited duration when a product originating from the other party is imported in such quantities and in conditions as to cause or threaten to cause serious injury to the domestic industry, or disruption in a sector of the economy or in a market. In such a case, safeguard measures may consist in the suspension of the reduction in customs duties, an increase in the customs duty (not above MFN rate), or the introduction of tariff quotas for the product concerned. Those measures shall be temporary, proportionate, and subject to a consultation mechanism between the parties.

West Africa also is also allowed to implement safeguard measures to protect infant industries. If a product, following the reduction in the rate of customs duty, is imported in quantities increased to such an amount that it poses a threat to the establishment of a “fledgling industry” or causes or threatens to cause disruption in a fledgling industry producing similar products, West Africa may temporarily suspend the reduction in the rate of customs duty or raise the rate of customs duty (again, not above MFN). Those asymmetric safeguard measures (i.e. available to West Africa but not to the EU) are exceptional in comparison with other FTAs negotiated by the EU.

Agriculture, fisheries and food security

The tariff schedule for imports into West Africa leaves most agricultural products excluded from liberalisation. The agreement is meant to foster agriculture in West Africa, also by liberalising inputs for agricultural production. Action in connection to the EPA Development Programme should help to increase productivity, competitiveness and diversity of output in the agriculture and fisheries sector. Food security safeguards can be adopted if the agreement results in difficulty for West Africa in obtaining the products necessary for ensuring food security. The agreement also foresees enhanced cooperation in agriculture and fisheries, based on regular dialogue. Areas for such cooperation are described in the agreement: they cover for instance the promotion of performing irrigation and water management programmes, the improvement of the storage and preservation of agricultural products, the establishment of a vessel monitoring system for West Africa, etc.

The most favoured nation (MFN) clause stipulates that the EU shall grant West Africa any more favourable tariff treatment that it grants to a third party. In a similar way, West Africa shall grant the EU any more favourable treatment that it would grant to a large industrial country (or group of countries). However, the MFN clause does not apply to preferential treatment granted by West Africa to countries of Africa or the ACP states, leaving the possibility, for instance, for further integration between African regions without any obligation to extend these preferences to the EU

Development and regional integration

The EPA is part of the EU and West Africa’s development strategy. Both parties consider that improving access solely to markets alone is not a sufficient condition for bringing about the profitable insertion of West Africa into world trade. Rather, both parties agree that this move should be accompanied by effective measures to spur development across the region. The EU and its Member States therefore agreed to accompany the EPA by supporting actions and projects linked to the development cooperation aspects of the agreement. A significant part of that support will come from the European Development Fund (EDF), especially from National Indicative Programmes and the Regional Indicative Programme for the next implementation period (2014-2020).

As outlined in the EPA (Article 54), the EU and its Member States undertook to finance the development cooperation aspect of the EPA for a period at least corresponding to the period of economic liberalisation in West Africa, as a means to accompany the EPA implementation. Furthermore, the EU and its Member States agreed to assist West Africa in raising additional funding for the development cooperation aspect of the EPA from other donors with a view to ensuring that the EPA promotes trade and attracts investment to West African countries so as to encourage sustainable growth and reduce poverty.

Les Wathinotes sont soit des résumés de publications sélectionnées par WATHI, conformes aux résumés originaux, soit des versions modifiées des résumés originaux, soit des extraits choisis par WATHI compte tenu de leur pertinence par rapport au thème du Débat. Lorsque les publications et leurs résumés ne sont disponibles qu’en français ou en anglais, WATHI se charge de la traduction des extraits choisis dans l’autre langue. Toutes les Wathinotes renvoient aux publications originales et intégrales qui ne sont pas hébergées par le site de WATHI, et sont destinées à promouvoir la lecture de ces documents, fruit du travail de recherche d’universitaires et d’experts.

The Wathinotes are either original abstracts of publications selected by WATHI, modified original summaries or publication quotes selected for their relevance for the theme of the Debate. When publications and abstracts are only available either in French or in English, the translation is done by WATHI. All the Wathinotes link to the original and integral publications that are not hosted on the WATHI website. WATHI participates to the promotion of these documents that have been written by university professors and experts.